Milton and Early American Politics

This project was created as the capstone for my undergraduate program in English and Political Science and has been revised periodically since. It is the basis for a potential future book.

Bill Mauldin, Will Eisner, Cartooning, and The Military Industrial System as an Agent of the Post-War Comics Boom

This is a project in development that I’ve left on the back-burner for the time being.

Bill Mauldin is, in many ways, the quintessential war cartoonist. His frank depictions of the emotional and psychological toll wrought on the combatants of World War II made him the youngest at the time (?) Pulitzer Prize winner at 23 and endeared him to his fellow “dogfaces.” And yet, Mauldin remains profoundly underrepresented in the field of comics scholarship. This owes a lot to the fact of his wartime cartoons being seldom reprinted since the 1960s, with the notable exception of the splendidly produced two volume box set issued by Fantagraphics Willie and Joe: The War Years[1]. It is also, to some degree, a product of the fact that his post-war cartooning took on a far more editorial bent, lambasting contemporary political figures and movements, taking a staunch stance against segregation, racism, anti-Semitism, nationalism, and a host of other contemporary ills which the audience, eager to put the war behind them, may have found less apolitically agreeable than his wartime work. In this essay, I will close read some of [AG1] Mauldin’s most influential and dynamic cartoons, setting [AG2] his work within the context of WWII cartooning. By examining Mauldin alongside his contemporaries Dave Breger (GI Joe) and Will Eisner (Army Motors, PS: Preventative Maintenance, and his more famous non-military work), I hope to refocus criticism on the novelty of Mauldin’s work and to encourage further critical attention to a woefully neglected body of work.

To this end, I gesture to the work of two contemporaries whose positions in WWII cartooning complement and highlight Mauldin’s unique input. Dave Breger, whose GI Joe strip eventually grew to inspire both the term for an army grunt, replacing the earlier “dogfaces” and a Hasbro toy line which continues to the present day. Breger worked at much the same time as Mauldin and was published primarily in Yank another military publication, and one which famously printed only a handful of cartoons by Mauldin, and those in minuscule proportion. Another contemporary whose career runs parallel to, but differs from, Mauldin’s is that of Will Eisner, a few years Mauldin’s senior. His work in the period in the preventative maintenance publication Army Motors eventually led to his creation of PS: The Preventative Maintenance Monthly (still published as of this writing) in the 1950s, for which he continued editorial work and cartooning, for over a decade. This triumvirate, while by no means the gamut of WWII cartooning, I argue represents the predominant modes of war cartooning in the 1940s, with Mauldin occupying the position of correspondent and satirist, in the vein of his contemporary and friend, Ernie Pyle, Eisner occupying the role of educator, and Breger resting somewhere in the middle, producing cartoons with a much more upbeat tone and conventional mien than Mauldin’s. [AG3]

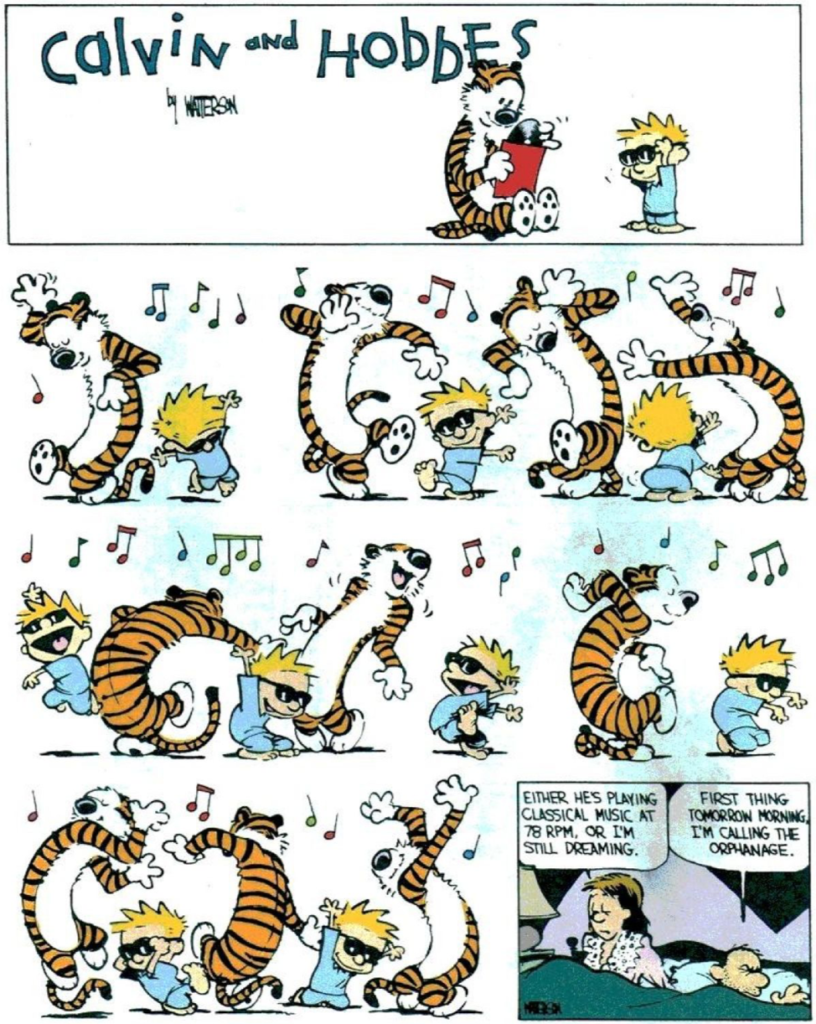

That Mauldin’s editorial work is neglected is, in large part, indicative of the two leading causes for the lack of critical attention to, particularly newspaper editorial cartooning. The first lies in the fact of newspapers are, essentially, ephemera. While the funny pages have a long history of being reprinted for later enjoyment in batch, editorial cartoons have historically been neglected for the reason that their appeal, unlike the timeless humor of gag strips[AG4] , is considered as ephemeral as the news items upon which they are based, and the newsprint on which they are printed. Obviously, the case has changed much in recent years, owing quite a bit to the crossover appeal of Garry Trudeau’s Doonsbury, but the gap remains.

Though Mauldin’s wartime work attracted far greater fanfare in the 40s and remains his trademark contributio[AG5] n, its lack of representation on the shelves of comics historians remains telling. One reason for this is that it, much like Eisner’s wartime work, was never really intended for civilian audiences. Though Mauldin’s cartoons were frequently reprinted in contemporary newspapers, and his first non-military published collection Up Front was a runaway best-seller, and Willie made the cover of the June 19, 1945 issue of Time Magazine, later years have not been as conducive to non-scholarly, or even scholarly, attention (Florida State 37). Mauldin released a number of book length collections of cartoons and commentary in his lifetime, though all are now out of print[2]. [AG6] Such generational hurdles are not unique to Mauldin, as both Breger and Eisner’s work of the period have attracted only scant attention[3] with Eisner’s also being eclipsed by his narrative work prior to and after the war, and by its technical nature[AG7] . Breger’s work has also been largely out of print since the mid 1960s though his reputation is bolstered by the fact of his popularization of the term “GI Joe” which has been the title of numerous loosely related comic strips, films, toys, and tv series since 1942. As this paper elaborates, however, where Eisner’s work in the period (for the military) has limited appeal to those who aren’t scholars of his oeuvre or enthusiasts attempting to repair and maintain vintage military vehicles, and where Breger’s cartoons are, though accomplished, largely the kind of gag-a-day strips common to the day, albeit with military dressing, Mauldin’s work, particularly that of the war years, is ripe for further critical attention and close reading.[AG8]

As early as June 19, 1941, Mauldin displays a knack for the brand of light satire which would become a staple of Eisner’s Joe Dope and preventative maintenance schtick, and which would fit well within the tradition of Beetle Bailey and Breger’s G.I. Joe. In his strip for the Oklahoma City Times while Mauldin was undergoing training with his 45th Infantry division of the mobilized National Guard, the reader is confronted with the nonplussed face of one of the many anonymous grunts [AG9] Mauldin employed before codifying the looks of Willie and Joe, who appeared in numerous early cartoons, though their characters would not be definitively outlined until about 1944. The private is being gently admonished by a superior, hands in pockets and be-slippered as are the privates, the other of whom, back to the reader, is doing laundry. [AG10] This private, Sneed, is in the process of washing his gun with a lathered brush and the caption below, spoken by the bemused superior, reads “You have the right spirit, Private Sneed. The technical details of cleaning a rifle, of course, can come later.” (Mauldin 54).

The situation of this cartoon is garden variety [AG11] and Private Sneed would recur sporadically in these early cartoons, often with differing appearances. Mauldin seems to have had a catalogue of names he employed for any number of otherwise dissimilar characters in the early years, Joe included, who in his earliest appearances is a Native American whose appearance, particularly when he dons his civilian garb (loin cloth and head-dress) along with his folksy mannerisms are the source of a few of the early cartoons’ punchlines. [AG12] Even at this early date, however, the reader sees the artistry which Mauldin is capable of when deadline and materials permit. The perspective is characteristically perfect, the product of a classical arts education, and the values in the cartoon are defined with zip-a-tone, the edges of which are clear in the later reproduction this writer has to hand. The expressivity of the faces on the figures’ faces are what, in many ways, distinguish Mauldin’s best work, and they are present here, such that the reader can clearly ascertain that Mauldin is a master both of “realism” in style and rendering, and also of caricature as a means of forwarding the “gag.”

In his first (of only six) contributions to the weekly Yank Mauldin works in a square, a format he would seldom employ in other publications. The subject, far from many of his Daily Oklahoman outings where he organically combines multiple cartoons with nebulous panel borders into a single rectangular page for his Star Spangled Banter, is firmly grounded in home-front drama. Two soldiers, both heavily bandaged, one with his arm in a cast and the other in a sling, are surrounded by civilians in eveningwear who seem to be celebrating the soldiers’ heroism. The soldiers look unnerved, and the one turns to the other as a waiter pours a bubbling glass of laudatory champagne, saying “I haven’t the heart to tell ‘em we got this way at the roller rink.” (Mauldin 189). Signed, Pvt Bill Mauldin, this cartoon was his first accepted to Yank and its success, as Mauldin attests, contributed to a “penchant for dumb gags” which would recur in his early career before his deployment and development of the more somber tone of the Willie and Joe years in Up Front (Mauldin 189).

By late 1943, Mauldin had more or less codified the single panel splash[AG13] with lower caption layout which would define his style. Mauldin’s cartoon, issued in the December 25, 1943, issue of the 45th Division News was printed in full color, courtesy of a Neapolitan engraver who worked laboriously from one of Mauldin’s watercolors. It is among the last of his conglomerate cartoons which proliferated from 1942[AG14] . It is interesting to note that the style Mauldin had adopted, with multiple distinct cartoons occupying the same space, had earlier characterized Breger’s G.I. Joe, and by the time this Christmas issue came out, Mauldin had begun to adhere more closely to Breger’s style with the stark intra-panel borders which separated the instances, a digression from his earlier experiments with the style where borders were more liminal[4] (Arden 26-7).

Mauldin’s genius is more fully revealed in his Up Front which introduced the running characters of Willie and Joe, the latter of whom, refined from an earlier, explicitly Native American, character of the same name, would sport a rounded nose, as compared to the aquiline-nosed Willie from whom he would be inextricable for the remainder of Mauldin’s career. In the May 5, 1944 Stars and Stripes Joe kvetches to Willie as bullets wing the barren tree outside their fox hole saying, “Wish to hell I wuzn’t housebroke.” A sentiment which Todd DePastino notes alludes to the reality of soldiers using their foxholes as outhouses, while also acknowledging the dehumanizing and simultaneously humorous reality of humans being reduced to the status of pets or animals by wartime necessity, which also casts light on the darker nuances of the term “dogface” for an infantry trooper (Mauldin 116). Three days later, Mauldin’s heroes, looking more tired than ever and with Joe looking particularly beleaguered, cigarette hanging with dismay from his lower lip, while being dressed down by a clipboard wielding and immaculately dressed superior before a series of signs signifying the overtaking of conquered territory by brass and military police including “Red Cross Officer’s Club” and “Ping Pong Tourney,” suggesting the privileges of noncommissioned officers and officers, over the infantrymen who did the legwork of claiming territory in combat. The officer in question is gesturing to Willie’s slovenly dress with a pencil, to Willie’s rebuff that “Them buttons wuz shot off when I took dis town.” (Mauldin 118). Two days later, Willie has his helmet pressed down over his eyes by a fallen brick and Joe is splayed with his helmet askew beneath the rubble of a bombed-out town and Willie admonishes his compatriot that “It ain’t right to go around leanin’ on churches Joe.” (Mauldin 119). This cartoon is one of many which emblematize Mauldin’s capacity for dark commentary, with the largest fallen beam of the church bifurcating the heroes from one another and the bricks disguising their limbs, suggesting the possibility that the bombs have not only levelled the buildings (leaving a house of worship indistinguishable from any other structure) but also left our heroes amputees. The devastation of a villa with walls missing and shutters hanging is juxtaposed with the classically cartoonish image of a man with his hat pulled over his eyes in Chaplin-esque discombobulation. Two days later, Mauldin reworked an earlier cartoon, one of the six published in Yank, depicting an infantry officer, portly and disheveled despite this, hand before his eyes, with a gun to the bonnet of his incapacitated Jeep (wheel bent inward) (Mauldin 120). The label on the number plate which reads cavalry is hardly necessary to the meaning, implying the progression from the cavalry (horse driven) of the prior world war. As DePastino notes, this was one of a number of cartoons Mauldin worked on around the same premise, revising it as he grew more proficient in his craft, to the end of his chief goal as a cartoonist, that a good cartoon should require no caption to convey its meaning.

It is suggestive of Mauldin as a visionary cartoonist, that so much of his philosophy, conveyed through his many interviews, most cited by DePastino in the collection or in his excellent biography of Mauldin, subtitled A Life Up Front,[AG15] predict later movements in comics art towards a move away from the dependence upon captions to convey meaning. Taking only a brief look at contemporary cartoonists’ and comics writers’ comments, one quickly finds that most, if not all, see the object of cartooning to be picture making with the least amount of narrative and dialogue captions required to convey the story. When one reads much of the work produced not only in the 40s, but up to the close of the Silver Age, wherein dialogue and captions often eclipse the art on the page, often contrasting inorganically, or worse, simply reiterating[AG16] , the meaning of the images, Mauldin starts to look more like the genius he undoubtedly was.

On May 17 of 1944 Mauldin scores value lines in a circle around the sleeping bag ensconced figures of Willie and Joe, that latter of whom is training his service pistol on a gigantic white rate [AG17] while the former has a gun shaped flashlight shone on the same, and with a second rat, head elongated to suggest intention and malice, at the base of his sleeping bag, ready to pounce (Mauldin 123). Of course, both soldiers, as is characteristic in these comparatively bleak depictions of wartime service, bear dispassionate, even ambivalent expressions while the caption, spoken by Willie, proclaims “Aim between th’eyes, Joe–sometimes they charge when they’re wounded.” Naturally this warning calls to mind the reality of hunting larger game like elk and bears who actually pose such a threat, while also suggesting the wartime reality that rats and the enemy are largely interchangeable and equally dangerous in like circumstances, carrying diseases, perhaps, rather than incoming bullets or mortar shells.

It should be noted, too, that where Eisner and Breger relied upon the caricature of the dopey enlistee haplessly bungling the best laid plans of superiors (for the purposes of humor or instruction to would-be imitators of such behavior) Mauldin’s military men are hardscrabble but humorous and disaffected everymen. Indeed, his Joe is more indicative of the standard issue infantryman than Breger’s, if only because Mauldin interacted with, indeed, was one of, the dogfaces. Breger, as Arden suggests, renders his GI Joe as a stereotypical college educated intellectual whose fallen on the luck of the draft as a 4F enlistee (46). Mauldin’s heroes also fall shy of the cartoonishly idealized brawn of Hasbro’s war fantasies, but they certainly aren’t incompetents, nor are they, despite representing everyone, simply anyone. Through the years of Up Front and earlier continuity, Mauldin layered many characters into his heroes, including, despite the evident racial insensitivity of Joe’s earlier portrayals as a Native American, the baggage attendant upon being a member of a marginalized group in American society forced, or otherwise compelled, to fight for truth, justice, and the American way[AG18] , which has never lived up to the equality ideal enshrined in the constitution.

In this way, Mauldin, perhaps unintentionally allies himself, not only politically, as he would in his post-war cartoons, but certainly thematically and ideologically with the wartime cartoonists in majority black periodicals, the most prominent and studied of whom, is Oliver Harrington. Harrington’s Dark Laughter follows African American soldiers in the war, enduring not only the harshest combat situations, but also the indignity of segregation and the inherent stratification of military hierarchy which in many ways accords exactly to socioeconomic and, de-facto racial hierarchies back home (Hopkins 14). Bootsie, the hero of Harrington’s strips shares an animus with Mauldin’s Willie and Joe in that he presents a wry, even subtly anti-authoritarian commentary on the ironies and injustices of military service. Israel Knox, in harmony with this sentiment, characterizes Mauldin’s satire by saying

Mauldin’s delight in the deflation of the ‘top brass’ stemmed from the deeper dissatisfaction with authority as such–with authority as divorced from the democratic sanction of consent, and with its inevitable stratification of men into castes (123).

Just as Mauldin was combatting the injustices of the military system as such, Harrington, and the real people whose struggles he depicted, were battling against the same forces and greater, as they had also to contend with segregation and racial inequality at home and abroad. It is no secret that, as in the civil war, African American prisoners of war were treated to firing squads rather than POW camps.[AG19]

To look at Mauldin, in this way, as a political cartoonist, a conclusion which seems only fair, considering his post-war editorializing and run for office, casts a new light on the significance of his commentary during the war[AG20] . Mauldin understood, or at least intimated, the injustices which his comrades in arms of other races faced, and reading his commentary in this light draws a starker picture of his dissatisfaction with the power structure at work. Famously, Mauldin had run ins, including a face-to-face dressing down with General George S. Patton, whose inclination, responding to two of Mauldin’s cartoons in particular, was to court martial and imprison him for insubordination and incitement to mutiny. Commentary abounds on the exact events surrounding the meeting, but, in brief, Mauldin defended his work by saying he felt his tweaking of brass and military hierarchy allowed men to blow off steam that might otherwise build up and result in genuine insubordination. Patton, by his own accounts in later interviews, including repeated threats, bought approximately none of this, but apparently conceded at the meeting’s close that “I guess we understand each other now.” (Mauldin Brass Ring 264). Mauldin would often defend his work this way, and DePastino notes that, at the time of the meeting, the precarious “blow off steam” excuse was all that had protected the sergeant for four and a half years (DePastino 194).

Black cartoonists on the home-front had the insulation of their papers’ limited circulation, a far cry from the affront which Mauldin’s cartoons presented as they were published in the military press[AG21] , but the affinity of the messages is undeniable. Mauldin reiterated, often, his convictions, which were ultimately affirmed by the Supreme Allied Commander himself, Dwight D Eisenhower, who wrote a letter to “Old Blood and Guts” and all other top brass ordering them not to concern themselves with the military press, effectively, as Harry Butcher, naval captain and aide to Eisenhower, leaving Patton having lost “the battle of Mauldin”[AG22] (DePastino 194). Mauldin elucidated his views in a number of ways over the years, but most effectively as quoted in Knox

Ours are not professional soldiers. They have recently come from a life where they could cuss and criticize their bosses and politicians at will. They realize that an army is held together with discipline, and they know they must have authority. They accept orders and restrictions, but because they are fundamentally democratic the insignia on the shoulders of their officers sometimes look a hell of a lot like chips. (122)

Mauldin’s gripe is one undoubtedly shared by black soldiers[AG23] and civilians in a number of ways, and it is telling that Harrington was effectively forced into exile in Europe after the war during the Red Scare while Mauldin’s criticism of the institution of HUAC and McCarthyite paranoia ultimately derailed his political ambitions. Chris Lamb uses Mauldin to illustrate the lenience afforded which was not extended to cartoonists the Harrington, though his work, in exile, was still circulated in majority black papers like The Chicago Defender and The Pittsburgh Courier (724-25).

At heart, however, some truth undoubtedly lies in the paranoia, not only of Patton (at least about Mauldin’s intentions) but of McCarthyism[AG24] and its intrinsic notice of the disparities which inflamed class and racial tensions and which its unconstitutional actions only exacerbated as those it persecuted (whether Communists or not and whether loyal to Stalin or not) rhetorically threw them for loops at the dawn of the age of mass-media circulation. The lesson, as in the case of the Hollywood Ten, was that attempts to censor the most erudite portion of society inevitably left the censors’ faces looking eggier than Easter Sunday. Perhaps the most telling suggestion that, at least Patton had got Bill’s number correct, is in the forward to Bill’s final book, What’s Got Your Back Up? where he muses wryly, “as for my wartime work, one of the few men in the Army with the perspicacity to see what I was really up to was General George Patton. When he tried to put a stop to me, somebody (I can’t imagine who) hollered ‘Free Press!’ and I was allowed to go on inciting mutiny under the guise of simple soldier jokes.”

Lucy Shelton Caswell talks more broadly about wartime editorial cartooning in America. While she reiterates Mauldin’s self-defenses, she minimizes the complexity of his work, writing that

The fact that Mauldin’s work was published in Stars and Stripes, a military publication (as well as being reprinted in civilian papers) makes it even more remarkable as a turning point in the content of mainstream American war cartoons. Mauldin editorializes about ordinary soldiers as they do their duty. His patriotism is unquestionable, but his cartoons do not glorify war or dehumanize the enemy. Far from stirring up wrath or hatred, the gentle[AG25] , ironic humor of these cartoons humanized battle and personalized the experience of war, and the ultimately had the effect of building support for the war, despite Patton’s fears

For one, she misses the parallel which was drawn by Patton himself, to WWI era cartoonist, Bruce Bairnsfather “whose ‘Old Bill’ cartoons revealed the absurdities of war a generation earlier” (Ribera 152-53). For another, she provides little evidence beyond the anecdotal to support the assertion that Mauldin’s cartoons supported the war effort. If anything, the human face Mauldin put to battle worked against the patriotic urge to commit firepower where diplomacy could possibly be availed of, and the depictions of war-torn Italy and Germany, in particular the cartoon, often discussed in critical approaches to Mauldin’s oeuvre, showing a soldier marching past a scowling woman within the smoldering remains of her home, with the caption “Don’t look at me, lady. I didn’t do it.” suggests the human cost of not just the second, but the first World War as well, and the punitive economic hardships which ultimately paved the way for the dawn of the Third Reich (225). Perhaps Mauldin’s cartoons humanized the combatants in the war, and perhaps his depictions helped to ease stateside uneasiness by painting a realistic but nonetheless gently[AG26] humorous vision of the combat zones their loved ones were fighting in, but Mauldin was far from a hawk, as his many cartoons lampooning the point value system of honorable discharge in the waning days of the European campaign attest to (326). This was a man who understood what he was fighting for, but quite evidently doubted the means by which it was being fought for.

In one of his intermittent non-Willie-and-Joe cartoons, Mauldin depicts a quarter of officers seated around battle plans which are being gesticulated to by a sour-faced three-star general in a non-regulation shirt, beer belly straining the confines of his hiked-up trousers (265). The caption reads “Hope I meet that guy in civilian life…” pointing to what DePastino calls a common military fantasy wherein the situational hierarchy of the military is again given away to democratic equality and the right to royally object, even violently, to the moronic demands of one’s would-be superiors. Not only does Mauldin foreground the minuscule differential in the power of the one three-star general as opposed to the three two-star generals, he also deliberately depicts the more powerful man, not only standing to create an artificial height differential with the sitting inferiors, but also rather inelegantly depicts the superior as the most slovenly, and most portly (and therefore farthest from combat ready) soldier in the bunch, a fact only highlighted by the screwed up features and eyebrow obscuring oversized helmet atop his head. He also has a sharply pointed nose, echoing the features of several of Mauldin’s depictions of Nazi commanders (205 and 322).

In this sense, Mauldin is unique, for, as he attests, Patton was onto something in his assessment of Mauldin’s motives. Unlike his contemporaries in the mainstream military press, Mauldin really did have legitimate questions about the way in which the war was fought, which, while they fell short of mutinous and certainly weren’t anti-war in the sense of arguing against the European campaign, were certainly tinged with his deep seated resentments not only of the class and social castes which military ranks imitated and reified, but also his deep unease with American society in general, a fact which, as Ribera alludes to in his dissertation, may have impacted the comparatively poor reception of his more overtly political post-war work (154). Like the black cartoonists publishing in black newspapers who were attuned to the war on two fronts which civil rights leaders were pushing and which The Courier, one of the leading black newspapers of the era termed its “Double V” campaign to topple fascism abroad and racism at home, Mauldin couched his deep unease in superficially anodyne humor (Hopkins 7). Comparatively, Eisner’s work of the period never approaches those questions of morality in war, though, in his own way, he would become an ally to the causes of civil rights and social and economic justice, and depict them favorably in his later work. Breger operated much more within the realm of humor strips of the time, scarcely straying into territory which might land him in hot water.

Mauldin’s “combat men did not fight the Germans by the Marquis of Queensbury’s rules; they shot the enemy in the back, blew him up with mines, and killed him in the quickest and most effective way.” (Mander 18)

Ribera 148 “Mauldin’s act of ‘resocializing’ the common soldier may be regarded as a fight against a larger enemy–the alienating and dehumanizing forces of society itself, exemplified by war, military and civilian bureaucracy, as well as mass media, whose representations of the war, while reaching all the way into foxholes, were not necessarily for common soldiers, not even about them.”

“If a political cartoon has the goal of influencing its audience with a glimpse of reason and insight, what Gombrich calls ‘momentary focus,’ Mauldin’s work aimed for something different, as his audience needed no convincing about their situation.” (Ribera 151)

[1] See also their collection of Mauldin’s post-war cartoons, Willie and Joe: Back Home.

[2] Up Front, from what this writer can discern, is the only one of Mauldin’s books which has seen multiple editions in its original form.

[3] Eisner’s Army Motors work has never, to my knowledge, been reprinted except in part in various biographies and retrospective volumes, while his 1950s work on PS has been the subject of one best-of collection and one self-published volume written by a colleague and friend and enlarged with retrospective celebrations by fellow comics professionals.

[4] See Arden, pgs. 26-7 for a description and analysis of Breger’s use of this style.

[AG1]Be more concise and active in your language

[AG2]Word choice. They’re already set there. Maybe “situate”?

[AG3]This is good information but was too much detail about Eisner and Breger for the introductory paragraph. I’ve done a little re-organization here to emphasize the stakes of your argument and your primary claim (lack of attention/Mauldin’s work is in its own way quite revolutionary)

The information in this paragraph shouldn’t stay here; it should probably be adjusted a tad and put before the P starting “As early as June 19th”

[AG4]Hmm, I’m not sure about this claim? There are certain types of humor that translate well but that might not mean they are “timeless.” Otherwise, wouldn’t things like Mutt and Jeff still be popular?

[AG5]To what? The wording is a bit odd.

[AG6]This bit could be more clearly structured

[AG7]Dangling participle

[AG8]Too much for one sentence

[AG9]But he gets a name here—not Willie or Joe but not quite anonymous.

[AG10]This is difficult to follow. Who is in slippers, who is standing, who is sitting, etc.

[AG11]Well; not quite. It is patently absurd. Is the absurdity garden variety for Mauldin’s strips?

[AG12]This note that his “civilian garb” is racist caricature seems like a dangerous thing to skip over so quickly.

[AG13]Is this term normally used when referring to single panel cartoons?

[AG14]I’m not sure what this means—what conglomerate from 1942?

[AG15]Again, this gets wordy and tough to follow

[AG16]“Contrasting inorganically” and “simply reiterating” seem like opposite to me, not levels on the same scale—as your sentence seems to treat them here.

[AG17]? misspelling? Word drop?

[AG18]Again, be careful with too many clauses. Don’t be afraid to break up sentences

[AG19]I’m willing and even want to go with you on this section, but considering you kind of skipped past a racist caricature earlier (though you mentioned it just above), it seems like a bit of a stretch to say that Mauldin is more aligned with black cartoonists simply because he was concerned about the injustices in the system. Perhaps a direct comparison of a Bootsie strip to Willie and Joe to provide further evidence would be more convincing that using a quote.

[AG20]THERE. That is a good way to state your thesis, I think. He can be considered a political, editorial cartoonist, even in the war papers while being a soldier. That’s an intriguing idea, because what does a political cartoonist in a military publication look like? Especially as you spell out that he is critical of the brass.

The idea of criticism/satire/editorializing + military publication is intriguing enough; add during WW2, then I go, “Oh really?”

[AG21]This could be stated more clearly.

[AG22]Another sentence that gets lost in the comma-clauses

[AG23]Again, with this thread you need to make the Bootsie connection stronger.

[AG24]I’m not sure how well I follow the McCarthy connection, especially considering Free Speech technically won here?

[AG25]This is perhaps the term you want to take down, yes?

[AG26]What is “gentle” about it? If he is, indeed, trying to incite mutiny…what would be an “ungentle” version of this joke?

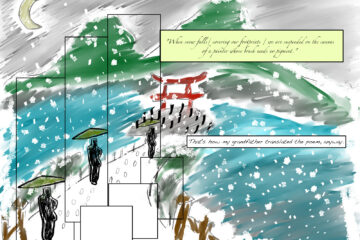

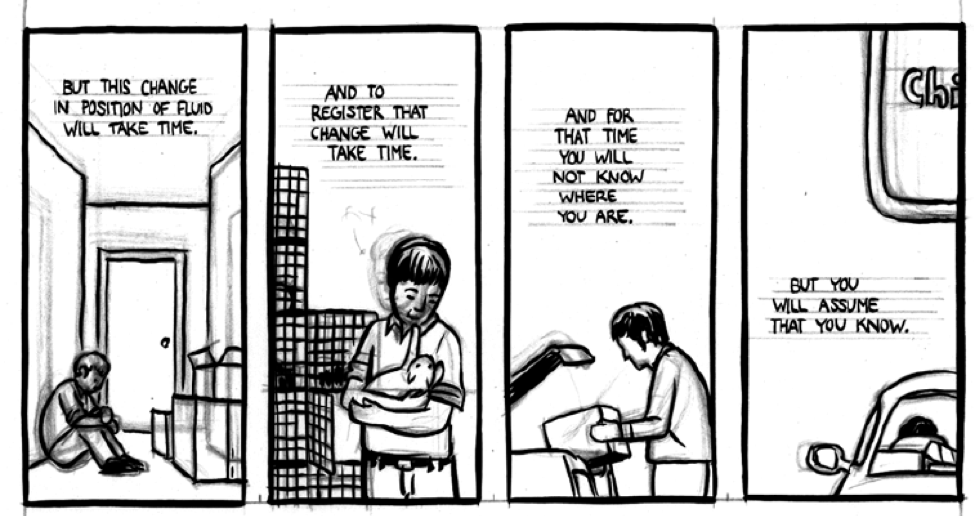

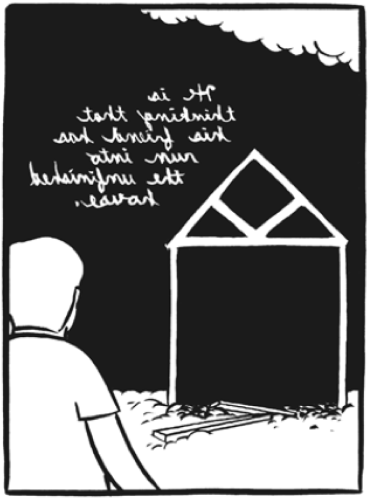

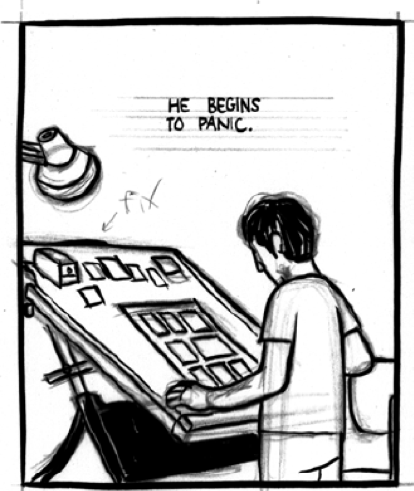

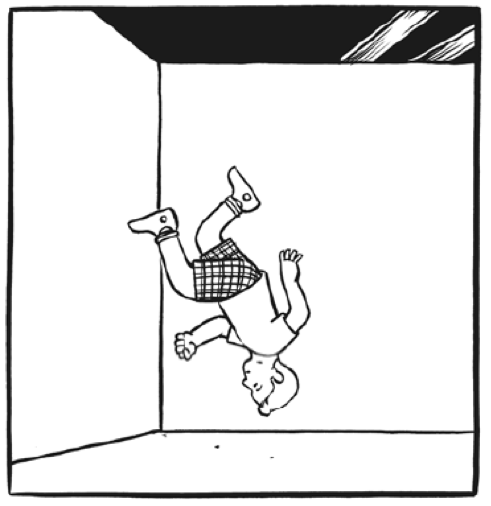

First Train Home

Created for Brian Michael Bendis and David Walker’s Creating Comics class at PSU. This is a full length comic created entirely by me, with the cover being partially sampled from a still from Hayao Miyazaki’s Spirited Away

The Trouble with Translation OR the Task of the Digitizer:

Incommensurability, Print, Digitized, and Digital Comics, and the Future of the Medium(s)

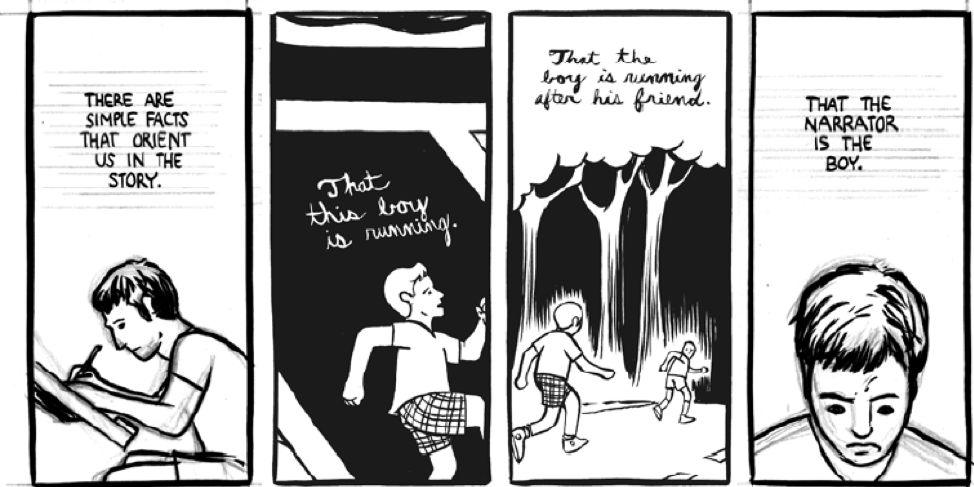

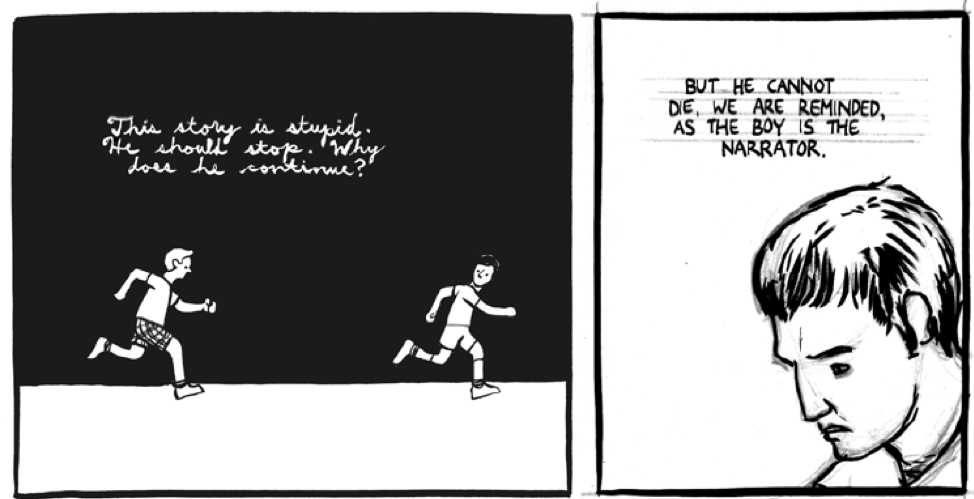

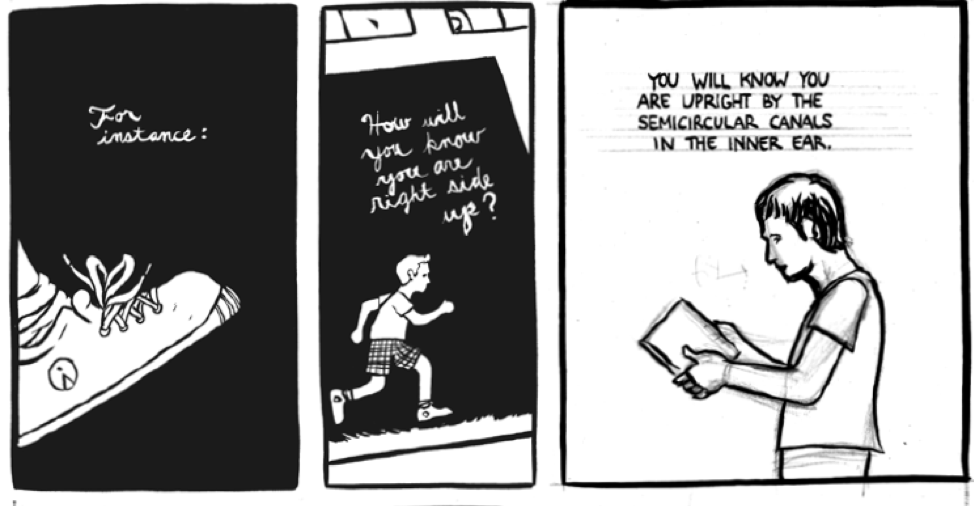

The purposes of this essay are twofold: first, to indicate the need for a dedicated branch of comics studies devoted to adaptation, translation, and transformation which addresses the unique facets of digital comics and acknowledges the compromises made to bring print native content to digital reading environments; and, second, to survey a representative crop of current (non-Marvel-and-DC) editorial staffers to assess their intuitions and intentions as this new medium experiences its uneasy birth. I have, elsewhere, constructed an argument for the incommensurability of print and digital comics content, based principally on my acceptance of Charles Hatfield’s “Four Tensions” which distinguish comics as a medium. The print comic, from the single panel cartoon to the multi-panel strip, to the comic book, relies upon what Hatfield terms “codes of signification; between the single image and the image-in-series; between narrative sequence and page surface; and, more broadly, between reading-as-experience and the text as material object” (132).1 When presented in a digital environment where the unit of the page is reproduced smaller or parceled out panel by panel for ease of viewing on a phone or tablet screen, the gestalt effect of the reader comprehending the page

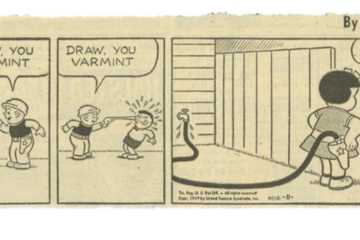

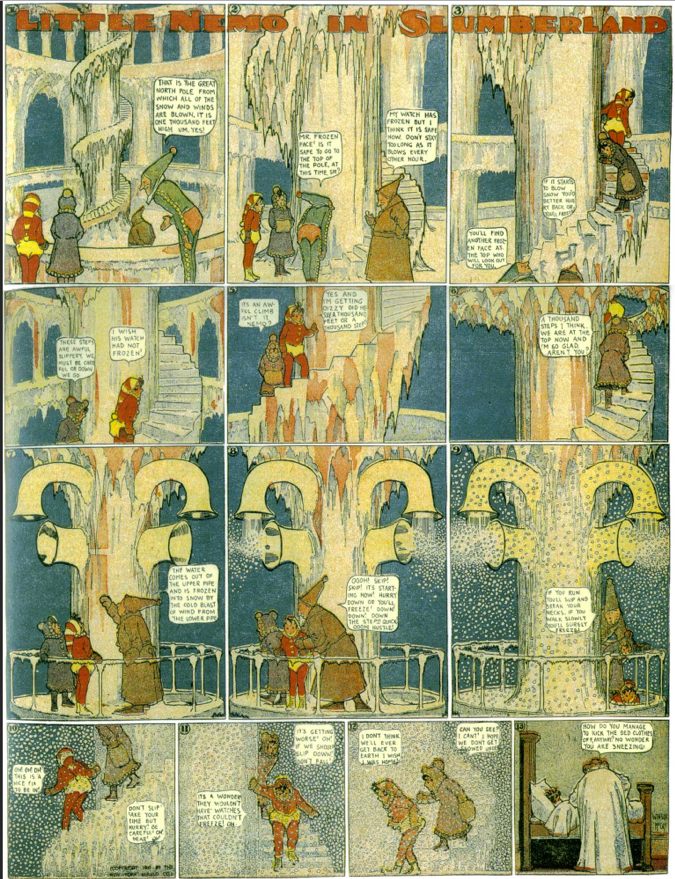

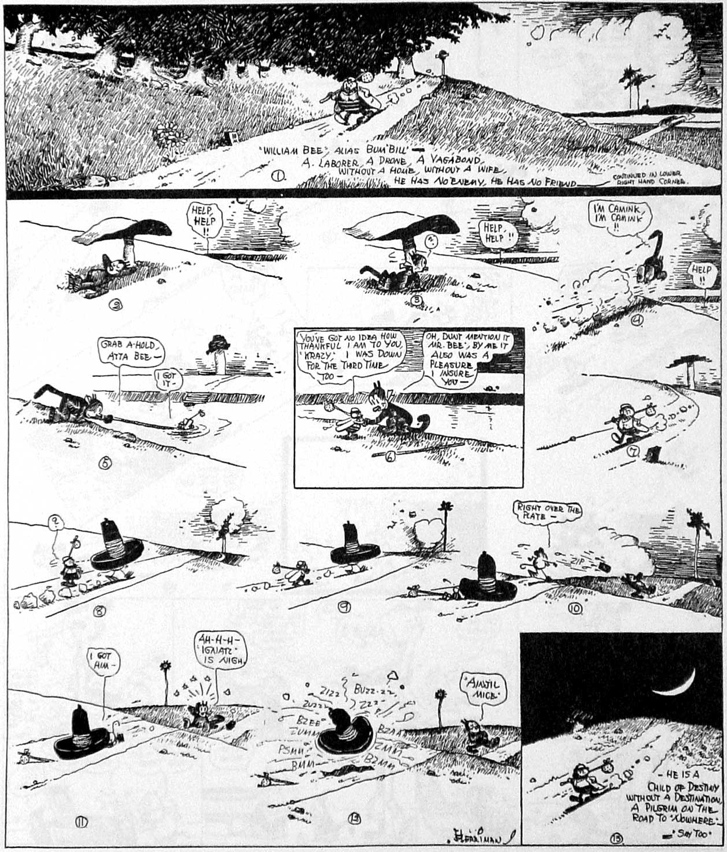

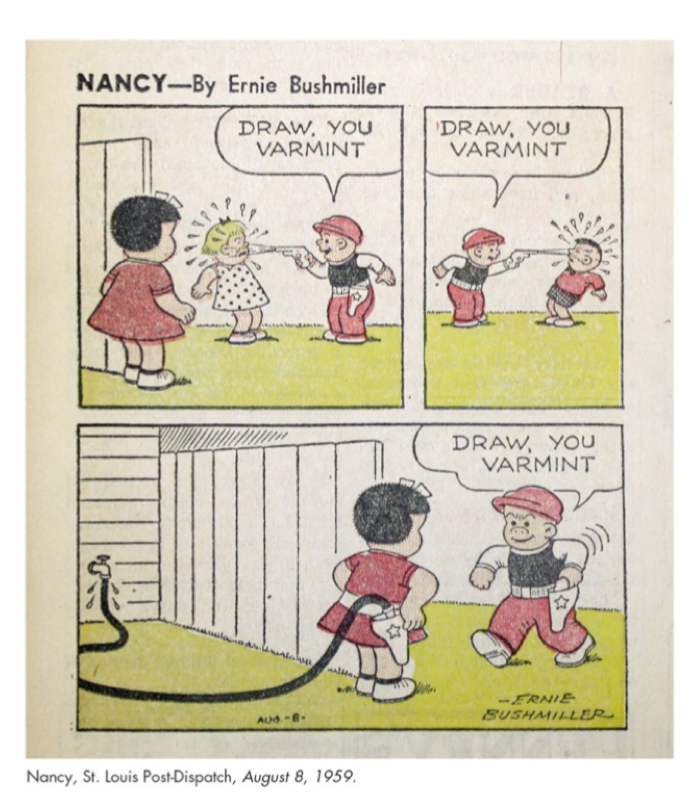

1 The single panel cartoon, I would argue, still fits these tensions because historically they are printed as a part of a broader page unit. An example would be a New Yorker cartoon set against an article which, though it may bear no relationship to the cartoon, is defined as an experience by the interruption which the image presents. The experience of reading a short story with such paragraph breaks is distinct from the experience of reading the same essay in a collection devoid of these interruptions. Even a cartoon like The Far Side, is most often presented on a newspaper page alongside other cartoons and strips. Their sizes relative to one another and arrangement impact when the reader will encounter them. In short, the page surface and the physical presentation remain key to their appreciation as a material experience despite the narrative sequence not necessarily being parceled out by panels. Single panel cartoons also benefit from the expectations of their multi-panel counterparts for much of their humorous punch. Punchlines are often implied to exist in a subsequent (though non-existent) panel. If Gary Larson shows us the pillow talk of a pair of praying mantises, the denouement, is forestalled, implied by the gestalt of the image-text as surely as it is in the incipient water-weapon showdown in the “Draw, you varmint!” Nancy strip which Newgarden and Karasik so lovingly dissect.

as a unit simultaneous with the panels as a narrative sequence is lost. Moreover, the text, presented in a digital environment, can never be a material object distinct unto itself because it is one of an almost infinite number of texts which can and will be presented in the same physical package. This is not to suggest that digital comics are in any way inferior, nor does it stand to reason that a translation to this environment from the physical page will render the product incomprehensible, merely different2. The purpose of this delineation, in this essay, is to draw attention to the importance of recognizing such translations as just that, translations. Publishers are already working to reproduce back-catalogues in cheap, readily available digital form and this massive recirculation of content which, until fairly recently was ephemeral and subject to disappear entirely except for the most diligent collectors when it went out of print has contributed to a democratization of “geek” culture, as the gatekeepers who rose in response to the shift to the direct market (which removed comics from spinner racks and relegated them to head shops where children and the cannabis-averse were less likely to encounter them, leading to the rise of “mature” comics as the industry driver (a

2 I hasten to add that I am not prescribing print or medium-specific fetishism, nor am I endorsing the lionization of the “original,” a tendency which many literary scholars exhibit. Originalism, as in law is limited in its utility, particularly because, like law, comics is a complex amalgamation of many different practices, traditions, norms, tropes, hierarchies, etc., and so pointing to an “original” intent, even when dealing with a cartoonist is a fool’s errand when one considers that, as in any creative medium, there are bound to be editors in play. No, comics are fundamentally collaborative, and so, in a manner of speaking, any given presentation of a comic is as legitimate as a production of a play. There is a case to be made for evaluating some presentations more highly than others and for critiquing them on the basis of their aspirations; no critic worth their salt would attend a traditional, bare stage Elizabethan production of Hamlet and dock it for a lack of pyrotechnics, but they would critique the polyester undergarments and period inappropriate accent work. The same is true in comics. It may be as legitimate to reproduce a Peanuts strip as a square of four panels as a sequence of four, given Schulz considered this expediency of publication design in his creation of the strip, though an argument could be made that the fact he drew the original strip on Bristol board in a four-panel horizontal sequence lends additional credence to the primacy of that presentation. Nonetheless, it’s up for debate and subject to its publishing context. Even an auteur in the true French sense like Hergé, the Belgian cartoonist behind the inimitable Tintin albums actually redrew entire stories and sections and authorized reflowing of panels for editions both at home and abroad, and most of the early stories were initially released in monochrome, though their contemporary preferred forms (evidenced by their continual reprinting) are the redrawn and coloured versions. Boutique editions of the “pure” original versions are available, too, as alternate, though not necessarily superior or truer, even in the estimation of the author who redrew and coloured them, editions. That’s not even mentioning the lettering which Hergé did himself for the original French language editions and which handwriting was recreated digitally for some foreign editions while, for others, typical computer fonts or native language hand letterers were employed. Each have their own inherent value and, as in Benjamin’s conception, asymptotically approach but never reach the purity of the original, albeit with the additional caveat that the “original” is a fallacy no more legitimate, in and of itself, than either conclusion in the interminable debate over whether George Lucas ruined or refined Star Wars to an original, but initially unreachable, vision with the special edition re-releases of the films.

trend we are only now seeing reversed as all-ages graphic novels resume their domination of the superhero market (evidenced by the ascendance of Michelle R. Wells to Co-Editor in Chief (though she subsequently returned to Executive editorship of DC’s Young Adult line after the departure of Bob Costas) (Johnston). The effect of scarcity led to the rise of aspects of fan culture which privileged long-time readers and made comics progressively antagonistic to new (young) readers, a trend the market has now seen for the folly it was. The rush to open these back-catalogues to the curious is profit motivated, as publishers, for the first time, have an extremely cost-effective means of distributing content which is unlikely to earn out a reprinting but which may have undergirded the story of the latest superhero blockbuster. But it also represents the advent of an era where the best and worst of the medium will be available to readers regardless of their ability to locate or afford a copy of Action Comics #1. It is important, however, for comics studies to develop as a discipline, that materiality be considered in literary analysis and such diligence requires that comics scholars and consumers demand that care be taken in re-presenting the original experience in a manner which is conducive to the digital environment, just as a translator of a text takes care to ensure that the spirit of the original is carried over into another language. I take this a step further, positing that the care required to re-present print-native content indicates that digital comics are, themselves, a unique medium and one which publishers ought to explore not merely as an expedient to monetize a back catalogue, but to develop the art-form and present creators with opportunities to exploit the capabilities of phones, tablets, and e-readers as material objects with which digital image-texts can collaborate to tell new types of stories and broaden the field of comics studies and the entertainment landscape as a whole.

I am indebted to comics scholarship, particularly that of Thierry Groensteen, whose work on delimiting the frontier of digital comics lends me the nomenclature for referring to native digital (as opposed to print native and adapted content). Groensteen developed the concept of adaptation from print to a digital medium in which the page unit is broken as a form of editing, analogous to film editing (Comics and Narration 64). Groensteen likens the process to observations on some of Enki Bilal’s work, in which the cartoonist created panels for a graphic novel as isolated units to be assembled into the final work (Comics and Narration 64). Naturally, the distinction must be made, that this was a practice devised and decided upon by the author, while the in-house or industry adaptation process of translation from book and page units to panel units is carried out by those whose investment in the work is non-authorial. Comics, in the U.S. especially, have long been an inherently collaborative medium, meaning that an additional cook in the kitchen requires only the additional credit and scholarly consideration. I hasten to add that, unlike Groensteen, I don’t worry for the loss of “the original” in the shift to digital art processes, such as practiced by Fiona Staples, wherein there is no “original” or “virgin” art to be displayed in galleries as an autonomous object. In fact, I would argue that this shift prioritizes the inherent sequentiality of comics art and helps to work through the ghettoization to which comics art has long been subjected. Comics as a collaborative medium can only benefit from the erosion of auteurist fetishism and the re-presentation of narrative art as fine art; I do not fret, as Groensteen does, that the loss of originals will prevent the formation of an archive or threaten the scholar’s ability to trace the material evolution of comics (Comics and Narration 65). If anything, the objectivity of computer files (pantone numbers in coloring, lack of handling deterioration, absolute pixel location values and scalability) and the longevity and reproducibility of digital files pose fewer threats of deterioration and concretize aspects of original presentational intent which obviate problematic aspects of materiality studies like fading, print error variations, etc. This all goes to say, I write from a perspective of fundamental optimism for the future of comics as what Groensteen terms a hypermedium, and digital comics in particular (Comics and narration 68). The possibilities afforded by digital comics and what Groensteen terms digitalized comics are exciting and the former, as this

essay will expound, may well hold the key to revitalizing an industry which has trended towards the moribund for the better part of the past several decades, in spite of the triumphal success of films derived therefrom. In Groensteen’s words, the frontier of digital comics redefines comics (as a whole) as “a hypermedium, orchestrating heterogeneous elements (text, still image, moving image, sound) and transforming the reader into an active user, a ‘readeragent’ according to the neologism coined by Anthony Rageul” (Comics and Narration 68). The hypermedium of comics, thus, embraces its inherent complexity as what many already view as a mongrel medium becomes all the more-so. Like any mutt, too, the medium is only strengthened by this inclusivity, but only when the scholar approaches the products thereof with appropriate care. How this care can best be taught and exercised by publishers in the facilitation of the creation of new works which embrace these diversities of form is a question addressed in the latter portion of this essay, in collaboration with those already engaged in the work of doing so.

My interest in defining this new medium has led me to ask the question of to what extent publishers and their editorial departments are already working to develop digital comics as a discrete medium and venue for the creation of entertainment product? Marvel has released several “motion comics,” generally as tie ins to their animated media: Ultimate Spider-Man, for instance. These utilize screenlike transitions such as the time on a digital clock shifting with a progression tap to signify the passage of time, instead of the comics native inter-panel transitions which reproduce a panel, like one showing a digital clock, with the latter panel showing the same time change. This digital only comics feature obviates the inter-panel closure which McCloud isolates as a unique feature of comics (though I, along with Dylan Horrocks, object to the role this plays in McCloud eliminating single panel cartoons from the realm of comics). If one wishes to be proscriptive of comics as a medium and NOT a hypermedium, such an element would disqualify the digital comic from consideration, but the analogous features of digital comics far outnumber their unique features and so considering them as a branch of a hypermedium seems more prudent.

Comixology’s proprietary “Guided View,” hereafter referred to as GV, has a similar effect on digitized comics as cinematic intra-panel transitions, substituting, in most cases, the movement of the eye from panel to panel, with a cross fade, reminiscent of a filmic or slide show transition. In more complex cases, where the print work is, in Kashtan’s terminology, “Kindle-proof,” more work may be required to approximate the experience of reading print in the digital environment. Kashtan, for instance, refers to Jason Shiga’s Meanwhile, a choose-your-own-adventure comic which was illustrated as a single, large canvas and which, in its print form, uses tabs and arrows to signal the page flips as readers choose their direction in the text (167-82). The text also, as Kashtan points out, has sections which must be randomly accessed by simply flipping through the book, because they are not linked by any story path originating outside these islands of narrative. This random-access component makes it extremely difficult for that experience to be replicated in a digital environment like GV, where narrative progression is deterministic, albeit prompted by finger taps or swipes. In this sense, Shiga is engaging with Lev Manovich’s conception of the database as the enemy of narrative. Interconnectivity is the underpinning of a database’s functionality. You must have a click path by which to access the logical antecedent to the precedent text. By stranding tangential narratives in the wilds of his dense canvas of a comic, Shiga highlights the especial capacity of print media to make use of human sensory intake and overload, a capacity which computers and their logic based language cannot encompass. In translating Meanwhile to the digital interface, the publisher created a version which is, essentially, scans of each page with minimal coding work to ease the process of accessing pages which are linked by tabs in the print text, forcing the reader to zoom in and out to appreciate content on the page when the screen is below a certain size, however, Shiga also worked with an independent developer to create a Meanwhile app which utilizes

highlighting functions (dimming the colors on unrelated narrative pathways while still allowing you to see them as adjacent storytelling units which might intrude on the chosen pathway) just as, in a choose-your-own-adventure novel where the reader can hold a finger in the previous page in anticipation of a gruesome demise). The app takes care to analyze the text and recreate as much of the experience (or as many of the experiences) as possible; however, such careful work is generally not undertaken for every print-native comic if for no other reason than that dedicated applications are too large and are inconducive to the centralized e-book/digital comic marketplace which is dominated by Amazon. Additionally, most comics are not as “kindle-proof” as Meanwhile. Yet, even a comic like Watchmen, built on a nine-panel grid that is, for the most part, unwavering throughout the 12 issue run and easily reproducible in a panel-by-panel slideshow format, makes use of the page as unit, most notably in the famous “Fearful Symmetry” issue, in which panel compositions mirror their corresponding panels at the other end of the book, converging at the exact center of the issue and underscoring the common themes of the narrative threads.

As I have established, the process of re-presenting the print experience digitally is fraught as a translation, and even the most comparatively simple task relies on thoughtful consideration which is antithetical to automation, the process which makes the production of e-books cost effective. As Kashtan notes, Comixology’s initial patent stipulated ownership of the process of converting to GV even via algorithmic isolation of panel borders (which would eliminate the need for human intercession, yet that technology has yet to roll out, even subsequent to Amazon’s acquisition of Comixology (116-17). They still tout their teams of dedicated professionals working to convert each issue and highlight that many of those whom they are employing to do the work are also comics creators. The degree of professionalism of these individual workers, however, is opaque, as is so much of Amazon’s business.

In the early days, before the almost total domination of the market by Comixology and Amazon, many companies, including Dark Horse, relied on editorial interns to do the digitization work. While most of these individuals, like Amazon’s faceless ideal worker, were and are passionate about comics, they were not employed as experts in the field and were not necessarily equipped to present the authorial intention of a narrative sequence. A comparison might be drawn to hiring someone to translate a novel using Google’s translation feature rather than hiring an individual who is fluent in both languages. The results might be comparable in many respects, but just because you have a human being intervening when obvious errors crop up does not obviate the problem of a lack of expertise (expertise being the ability to most closely approximate the intentions of the original creator(s), to paraphrase Benjamin’s “Task of the Translator.” In this paradigm, the humans are essentially content screeners, akin to Facebook’s hordes of content flaggers who tag content like graphic violence, fake news, and pornography.

It is unlikely, however, that it will become cost effective for companies to employ subject experts in each product they digitize to carry out that work, and so some degree of compromise is necessary. The opportunity presented, however, I believe will be remunerative and a way forward for comics publishers who are facing declining direct sales and an uncertain future in the bookstore market. That opportunity is to embrace the technologies being used to translate print content and consider those techniques as unique storytelling tools which might be the better applied in content created explicitly for digital presentation, whether it originates as hand-drawn art or not, as in the Enki Bilal example from earlier.

At the moment, the “big two,” DC especially, publish what they refer to as “Digital Firsts,” which are issues and series of comics which are distributed only digitally until they hit a sales threshold which justifies printing them either as single issues, or, more commonly, as trade paperback collections. To treat such projects as simply research and development or as a market test

for content, however, seems wasteful; just as the fact that Warner Brothers and Disney, who have acquired DC and Marvel respectively, treat their comics divisions primarily as intellectual property generators for their juggernaut film production departments seems a crass treatment of a medium. Put simply, just because one’s primary use for a shovel is as a bludgeon does not mean that the underlying value of a technology for piercing and moving ground powered only by human strength should be ignored. Publishers would be wise to seize the opportunity to diversify their comics offerings by embracing the unique features of the digital environment and using the advances in presentation and app development to attract new talent to comics as a hypermedium.

Digital interfaces offer untold opportunities to expand the possibilities of the medium of digital comics and even failed experiments like Marvel’s foray into augmented reality “AR” which involved scanning hidden codes on comics pages to reveal bonus content ranging from extra panels, to backup stories, to bonus material like creator interviews and sight gags or hidden advertisements have value as barometers for new types of content and the markets therefor. The problem with the aforementioned experiment was the interruption to the reading experience (forcing the reader to take out their phone and open a proprietary app while reading their physical issue), not to mention the shelf life of product support. Not all AR content was guaranteed to be hosted in perpetuity on Marvel’s servers and so creators were hardly likely to risk obsoleting their work by concealing meaningful story elements where readers might be disinclined to explore them or lose access to the ability to do so after a period as short as a few months. In a comics culture of so-called “trade waiting” where customers will frequently wait for larger collections of single issues to be published so that they can consume the story all at once, that obsolescence was all the more daunting. Such an experiment in what I would call “advent calendar storytelling” might find far greater success in digital comics where such a feature could be built into the reader application and thus obviate the interruption to the experience of the story presented by having to pull out a phone and open an app.

When you are already in the interface, the augmentations to reality become a part of the reality, rather than a gimmick, although Amaranth Borsuk and Brad Bouse present a similar conceit, far more effectively done in their Between Page and Screen, precisely because the interaction between the print and the computer is a gestalt rather than the comparative compromise of Marvel’s AR, which simply added to an already complete story and failed to justify its existence as a result.

Some similar forays into digital-first publishing were successful, however, with the comic series tie-in to the Injustice: Gods Among Us video game becoming popular enough that DC has now printed the material in a number of formats including “premiere” hardcover collections. Among the early crop of digital firsts, Injustice was developed in half page units to make the page presentation landscape for e-readers and so that the eventual print version would array these half page units vertically as normal pages (albeit composed of two page units) but this, of course, made it all but impossible for the writer and artist to use features like the splash page or double page spread in presenting their material, much less something like a fold out spread of more pages. All these expansions of the canvas, had DC committed to the product as digital native would have been open to the creators, but the decision was made to ensure that the content could eventually be printed in traditional comic book format, a constraint of which the creators took full advantage but which could also have been an opportunity to seek out creators with ambitions to create comics that don’t fit or work as well (or at all) with print standards. As discussed in the latter portion of this essay, the success of the market in years to come will be predicated upon the diversity of content to match an expanding audience, so compromises will be as valid as radical departures from the norm and both should be undergone where the talent has a clear vision and editorial the capacity to help realize that vision. Kashtan notes that Kramers Ergot, an irregularly published independent anthology which has had a number of publishers over the years, not to mention sizes and formats, had an entire issue which was printed at too large a size for even the largest mechanized binder, necessitating that each finished hardcover be hand bound (43). Comics is rife with such medium expanding projects and visions and for publishers to remain relevant, it seems obvious that the opportunities afforded by the democratization of technologies and the rise of web-comics should, to some extent at least, push publishers to expand their range of digital products to correspond with their experiments in print and hybrid forms of the two.

To that end, the remainder of this essay is dedicated to a critical engagement with the results of a series of interviews with editorial staff at a number of publishers outside the “big two” who I have excluded on the basis that my interest lies primarily with evaluating the digitization and creation of content which is creator owned “meaning IP not owned by the publishers” although this is not necessarily true in the cases of Dynamite, IDW (which pursues licensing deals), or Dark Horse (which also licenses outside properties). The limitations of these viewpoints and my engagement with them, is straightforward, in that the sampling is non-representative and draws upon only one department in the creation and publication of comics, albeit the department which liaises with all others. The insights I derived from these interviews are not, by any stretch of the imagination, intended to present a holistic prognostication about the future of comics as a hypermedium. They are meant only to provide a snapshot (limited, definitionally, in scope) of the industry today and to the extent I draw conclusions and make recommendations about paths forward, they should be taken in the spirit of scholarly argument. It should also be noted that where information was privileged or possibly compromising to the individual interviewed, I may anonymize their response in accordance with journalistic ethics.

…

Works Cited

Benjamin, Walter, et al. Illuminations. 1st Schocken paperback ed., Schocken Books, 1969.

Borsuk, Amaranth, and Bouse, Brad. Between Page and Screen. 1st ed., Siglio ; Distributed to the Trade by Artbook/D.A.P., 2012.

Groensteen, Thierry. Comics and Narration. University Press of Mississippi, 2013

Hatfield, Charles. Alternative Comics An Emerging Literature. 1st ed., University Press of Mississippi, 2005.

Horrocks, Dylan. “Inventing Comics.” Hicksville. June 2001. http://www.hicksville.co.nz/Inventing%20Comics.htm. Accessed 9 December 2020.

13

Johnston, Rich. “Marie Javins and Michele Wells Are Editors-In-Chief Of DC Comics.” Bleeding Cool. 14 August 2020. https://bleedingcool.com/comics/jim-lee-talks-dc-comics-bloodbath- to-hollywood-reporter/ Accessed 9 December 2020.

Karasik, Paul, Mark Newgarden, Jerry Lewis, and James Elkins. How to Read Nancy: The Elements of Comics in Three Easy Panels. 2017.

Kashtan, Aaron. Between Pen and Pixel: Comics, Materiality, and the Book of the Future. The Ohio State University Press, 2018.

Manovich, Lev. The Language of New Media. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press, 2010.

McCloud, Scott. Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art. HarperPerennial, 1994.

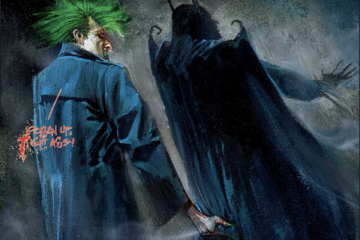

Sublimity and Sublimation:

Aesthetics and Aestheticism in the Batman Canon

This paper considers Batman as the prototypical sublime figure in modern fiction. Accepting the precept of Longinus, that fiction is the best (popularly available) means of transmitting and replicating a sublime experience, I consider the Dark Knight as a dualistic figure, both Bruce Wayne and Batman, the one a paragon of social virtue in a capitalistic and hierarchically divided society, and the latter who, in descending to the level of the criminals with whom he wages war, in fact raises himself to the status of moral paragon in the Kantian sense. Batman, more than this, also encompasses a Burkean understanding of the Sublime as an experience of terror, whether it’s enlightening or not. By eclipsing the system of laws and regulations which fails to enforce a social order that agrees with his conception of justice, Batman serves as an example to the people of the city of what is possible, and internalizes his own sublime experience of trauma, which I examine first in this paper, from which event he derives his moral compass, in a nod to the edification aspect of sublime experience in Kant’s understanding. From there, I consider the nature of Bruce Wayne/Batman’s dual identities and their implications for his embodiment of sublimity, before considering his relationship to the city and the urban sublime. In the final section, I close read the relationship between Batman and the Joker as a possible source of sublimity which ties them together in an eternal conflict which has literary precedents across human cultures.

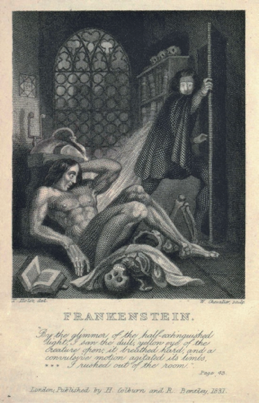

1: The Traumatic Sublime – Origin Stories

An alley, a man, a gun, pearls, and a boy watching his mother and father die. This is the story of the Batman, told and re-told in every medium available. The angle on the event changes, the particulars, the narration, but the crux has remained the same since Bob Kane and Bill Finger set it to newsprint in Detective Comics issue 33 in 1939. Recoloured for the first issue of his self-titled series the following year, the event of Bruce Wayne’s parent’s murder proceeds in the space between panels to a candlelit image of Bruce, knelt in prayer at his bedside, described by the narrator as “a curious and strange scene,” swearing by the spirits of his parents to avenge their deaths by spending the rest of his life “warring on all criminals.” [see figs. 1-4]

In the original story, the inspiration for Batman’s winged namesake and inspiration doesn’t come until he is older, however in most subsequent versions, Bruce’s fixation on bats is prefigured by an earlier trauma, usually falling into an old well that leads to the caves beneath Wayne Manor. In Frank Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns, the story is told in dream narrative, as Bruce, like Carroll’s Alice, chases a rabbit down a hole, and meets the force which will determine the course of his life thereafter. [fig. 5] Another, much more recent version of the story is told in Brian Azzarello and Lee Bermejo’s Batman Damned. Again, told in dream narrative, the young Bruce confronts a demoness. Wide eyed, he is frozen as she holds a dead bat, wings spread, to his naked chest, bathed in moonlight. [fig. 6] Regardless of the storyteller’s individual choices the wealth of symbolism to be gleaned from Bruce’s chosen totem, remains a touchstone for much of the better work done with the character.

Typically, the soon-to-be broken family are emerging from a movie theater, and often the film they’ve been to see (whether they’ve left early or not) before they enter the fateful alley, is The Mask of Zorro. Whether it is the 1920 or the 1940 version, thereof, depends on the requirements of the broader story (Borsellino 138). Regardless, Batman’s chief creative force, Bob Kane, was a fan of the Douglas Fairbanks portrayal of the character, and used Fairbanks’ portrayal of Robin Hood for the inspiration of Batman’s boy wonder sidekick, and his trademark costume (Borsellino 138). The question of inspiration and appropriation in Batman is tricky, and only adds to the sublime nature of the character, able to exist not only as the double life of Bruce Wayne/Batman, but also able to exist in innumerable iterations, from camp to gritty, and to age, de-age, and remain frustratingly un-aged for decades. Even within his own mythos, the Batman inspires the Batman, with a notable instance in the early radio drama featuring a caped hero who inspires young Bruce, The Grey Ghost, voiced by none other than Adam West, who in 1966 would assume the role of Batman himself (Borsellino 138).

This relationship to the audience allows Batman to transcend the page and become meta-textually greater than a simple, branded, comic crime fighter. At its core, the Batman canon is deeply indebted to both the masked heroics of the Scarlet Pimpernel, and the The Shadow series of pulp novels (Steranko). Growing from this tradition, however, Batman has come to signify far more through his myriad contributors and iterations from comics, to film, tv, radio, novelizations, children’s media, and the relentless multinational marketing appetite for his signature image. In the endurance of his property in the cultural conscious alone, Batman should be considered a sublime figure.

What lies at the root of this sublimity is trauma. As Dr. Michael Brody, a psychotherapist suggests, the “individuality of each superhero” is rooted in the sequela of trauma (105). Each hero confronts their own traumatic source: Superman his destroyed planet, Wonder Woman the death of her lover, Steve Trevor, Flash the deaths of his parents. That trauma lies at the heart of their resolve to be super-heroic. In this sense, as Brody puts it, Batman did not “choose his life’s work–it chose him!” (105). If we look at Batman’s beginning as the precise moment of his parents’ deaths, we can see how the senselessness of the violence would instill a resolve to do good, but it is hard to imagine it precipitating the kind of resolve which costumed heroics would seem to require. For this reason, many later iterations of his origin suggest that young Bruce already harbored a strong sense of right and wrong which was galvanized, rather than created, by his parents’ murders. Bruce’s grief for his loved ones did not drive him mad or result in many of the symptoms associated with childhood trauma, Dr. Brody notes, because “external traumas can be converted into internal ones if they connect with fulfillment of either deep-seated anxieties or wishes” (107). Precisely because Bruce, as Frank Miller portrays him, went into the fateful showing of Zorro, already a swashbuckling, justice minded, child, precisely because the moment of violence occurred after both the earlier incident of meeting the bat in the cave, and the immediate sight of a bat against the moon before the arrival of the mugger, the reader is forced to conclude that the potentiality of Bruce’s assumption of the Batman cowl, was already present. [fig. 7]

The question of trauma as the motivator for Batman’s actions is interesting, however, because his method of coping is not, as many have suggested both in the fictional world and our own, because Bruce is demonstrably insane. Robin S. Rosenberg conducts an extensive review of medical diagnoses which Batman/Bruce Wayne might fit the criteria of, concluding that the closest match, and that an incomplete one, would be Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, and that unlikely because his flashbacks are memories normally retrieved rather than the result of sensory stimuli (see the sequence of word association in Morrison and McKean’s Arkham Asylum) (149). As he elaborates, “Memories, flashbacks, dreams, or nightmares are all ways that a traumatic situation can be re-experienced. For this criterion, however, these re-experiences must be persistent, distressing, and intrusive,” and in Bruce’s case, they are not. (149) Moreover, because the risk of PTSD is dramatically lowered in situations wherein trauma can be rationalized according to one’s experience of the world, Bruce is less likely to experience PTSD than most because he consciously derives meaning from the traumatic event and incorporates it into his sense of being and life’s purpose (Rosenberg 153). Perhaps Bruce suffers from what Brody terms death guilt, but this is unlikely because he could not reasonably conclude that he would have been able to save his parents except by altering the choices which led them to the alley (108). Brody goes on to suggest that “Bruce’s premorbid personality was intact enough to bear any blow, and hence his quick recovery,” however the overwrought nature of his eventual resolve to war on criminals suggests that his reaction is compensatory (109). The adult Batman identifies with the criminal element and usurps its position of power through similar, but altered means, namely his no-kill moral code (110).

Another interesting aspect of Batman’s traumatic sublimity is its close association with omens and the symbolism of the bat. Dr. Brody talks about a number of patients whose traumatic experiences gave them a super-heightened sensitivity to symbolism associated with it. This could include details like seating arrangement prior to the moment or a mother’s failure to kiss the survivor goodbye right before. These associations became points of compulsive obsession linked intrinsically in the patients’ minds with the moment of trauma to the point of superstition. It is interesting to note Batman’s characterization of criminals as a superstitious and cowardly lot, when his own desire to manipulate events through pseudo-foreknowledge is the basis for his costumed identity in many stories (Brody 112).

In any case Batman’s sublime nature is rooted in trauma. Perhaps, as Tim Drake, the third Robin comes to think when his own parents are murdered, trauma is the price of entry for anyone wishing to become super-heroic (Borsellino 142). If anything could serve as evidence in the world of Batman, however, it would be the fact of his first sidekick, Dick Grayson, having a near identical origin story, his parents murdered by a thug before his eyes. The key difference in this case, of course, is the addition of Batman as a surrogate parent to help him channel his grief into a super-hero career. Even the arrangement of Grayson’s parents’ bodies, in most instances, is consciously rendered to evoke the same instance in Bruce’s past. [fig. 8 and 9]

In confronting “the chaotic, violent, and seemingly inexplicable natural world,” Whitney Borup argues that young Bruce’s “powers of reason begin to detect the limitations of his sensible knowledge.” (92). From this experience, he constructs a view of the world in which by physical and mental prowess, he can exert control over the external war. Borup talks about how “shadows illustrate a conception of knowledge common in the Enlightenment era, depicting the natural world as the darkness that threatens to overpower the light of human reason.” (92). She relates this to Burke’s claims about how in darkness it is impossible to gauge the extent to which one is safe or imperiled. Bruce’s experience, as illustrated graphically in the first iteration of his origin story, shows him drawn out of the world he inhabits; after his parents are murdered, the cityscape giving way to blocks of solid colour accentuating the anguished look on Bruce’s face. That he becomes Batman and takes on the role of protector of Gotham, Borup argues, far from tying him to the community, “instead, isolates him” (Borup 93). While I argue that he ties himself to the physicality of the city, if not the populace, Batman’s war on crime contorts his moral code into an obsession which in its monopolization of his life allows him to become a sublime embodiment of the antithesis to the chaos of the world. His methods, however, are those of the criminal underground, such that, as Borup argues, “Bruce’s rational method for vengeance guarantees his permanent association with criminality” (93).

As a hero, Batman “experiences and then embodies the sublime” ( Borup 87). By confronting the irrational violence which was visited not only upon his parents but which has been repeated again and again, in the lives of those he knows and in the city at large, Batman comes to enact that sublime moment, and this enactment thus “affirms his rational power to arrange nature according to his ideas of justice” (Borup 87). Batman comes to rationalize his use of violence against the criminal elements in Gotham as an opposition to the chaos represented by irrational violence. It is “Batman’s rationality, not his physical body, that constitutes his effectiveness as a hero” (Borup 87). The”sublime logic” which Batman represents, allows Batman’s writers and artists to play with the moral ambiguity of his actions (Borup 88).

Batman embodies the sublime, too, in the way he physically presents himself. He may, as Borup suggests, feel, “as Kant says,” his superiority to nature within [himself], and hence

also to nature outside [him]” (97). By assuming the appearance of his totemic self, he strikes terror into the hearts of those who would inspire terror. He is described often, even in early comics as “avenger of evil,” “cowled shadow,” “eerie,” “strange,” and a “weird figure of the dark” (Borup 97). What is sublime in his assumption of this role is that he usurps the position of the darkness and turns it to a force for relative good.

2: The Picture Of Bruce Wayne – Duality and the Dark Knight

The duality of Batman’s identity makes for a fascinating character study. In Bruce Wayne, billionaire playboy, Batman concentrates those aspects of himself he most reviles, namely his shallow romantic urges, his privileged excesses, his self-directed interest, and, most importantly, his simple humanity, namely those parts of his identity which fall short of the standard he sets for Batman. Quite often this duality creates situations in which Batman and Bruce Wayne must actually be at odds with one another. In a recent story, Tom King, in Cold Days, has Bruce Wayne selected for the jury of Mr. Freeze, who is on trial with only evidence provided by Batman to convict him. The story, coming on the heels of Batman’s aborted marriage to Catwoman, suggests that Batman’s grief led him to a hasty and unfair conclusion which Bruce, his other self, has come to regret. The story, told in the style of 12 Angry Men, pits Bruce as Juror #8 against fellow jurors more than willing to accept the facts of Batman’s evidence on their face. This dualism in Batman’s self has allowed for a number of such intriguing stories, and in its complication of the Dorian Gray plot, turning the portrait into an identity and making it impossible to tell which self is the true one, Batman is able to suggest not only an alternate identity, but an entirely alternative self.

In some storylines this drama plays out psychically as an opposition between Bruce and Batman. In Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns, Bruce seems to consciously wrestle with a separate entity which chastises him as “puny” “small” and “nothing–a hollow shell, a rusty trap that cannot hold me.” [fig. 10] This is the pivotal moment in Batman’s return to the city after a decade of retirement, and just beyond the windows, rendered as eight of the panels in the sixteen panel grid structure which Miller uses throughout the series, a storm cloud bursts into the margins along with the tail of Bruce’s dressing gown. He topples a statue in a rush to the shower, which itself suggests the nascent rains from the clouds dominating the top of the page. In a more literal rendering of this conflict, Batman Damned, shows Bruce pursued by the grasping suit, animate of itself. [fig. 11 and 12] The open portion of the cowl, devoid of its inhabitant, contorts into a birdlike gaping mouth, the nose piece suggesting the beak of a bird of prey, the kind which eats bats, and the extended hand is claw-like. The next page, a splash, shows Bruce bowed at the feet of the suit which is set into an alcove suggesting a sarcophagus. The suit is bathed in blue light from below, and red from above, lighting the cowl in a devilish hue, complete with ears that take on the appearance of horns.

Much like Milton’s Lucifer, “light bringer” and chief of the seraphic host, Bruce Wayne is a paragon, born into and made by both luxury and (as a product of their deaths before the ascent of his reasoning faculties) the unimpeachable nature of his parents’ character as benefactors of Gotham. In descending to the level of the criminals who claimed his parents’ lives, Batman becomes a kind of inverse of Milton’s Satan in that his “fall” from grace is made, rather, a means of ascent not to the vagaries of old monied self-righteousness, but to the super-heroics of Nietzsche’s imagination, even becoming the sole human (excepting the alien enhanced Hal Jordan, of earth as Green Lantern) in the original roster of the Justice League. It’s interesting to speculate, as street names are often used to honor comics professionals and influences within the pages of D.C. books, about the significance in Geoff Johns and Gary Frank’s Earth One origin story for Batman, of a street called Milton, which given its disaffected prostitute and porn shop, suggest a relationship to the Hell, if not the poetry, of Milton. [fig. 18] Ross Chiasson, too, notices this connection between Batman and the sublimity of the unholy forces which, by casting Gotham as a hell in need of harrowing, he allies himself with. Certainly these allegories are present in the above moments of Damned, and in Bruce’s candlelit declaration of war from 1939. These implication will be further explored in section four.

3: Gothic Gotham – Batman and the Urban Sublime

But what of Batman’s aesthetic considerations. His sublimity is rooted, as it must be, in something beyond the pictorial, however the conscious inclusion and evocation of the classic gothic aesthetic, even into the name of the city, Gotham, points to an influence that requires address. That the city, rather than nature, becomes the sight of sublimity, Pramod Nayar alleges, is because “Twentieth century versions of the Gothic have relocated many of these atmospheric conditions of emptiness, threatening settings and dangerous creatures to the city, as exemplified in numerous filmic and literary urban Gothic works (from thrillers like Brett Easton Ellis’s American Psycho to the cyberpunk fiction of William Gibson and films such as Blade Runner or