Dustin Prisley

ENG 507 Romanticism and Translation

Profs Beer and Hunt

March 23, 2019

Illustration as Translation in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein

At the intersection of romanticism and translation is Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, itself the epochal novel of the Romantic Period, and often subtitled as such, most notably in its first stage production. The novel is intimately tied to the works from which it draws, perhaps most prominently, Coleridge’s Rime of the Ancient Mariner, the Dore illustrations to which inspired Bernie Wrightson’s illustrations to the novel, close readings of which form the crux of this essay. [MOU1] The question this paper seeks to address, in the vein of a number of works which address what Shane Denson terms the “plurimedial” nature of serial texts [MOU2] (532). Denson applies this moniker to works which, like Frankenstein, have long afterlives across various media, such as Sherlock Holmes, and which accrue “non-diegetic[MOU3] ” attributes from each iteration, creating, in effect, a canonicity that includes, but is far from dependent upon the original text[MOU4] s. I approach Denson’s arguments as they pertain, specifically, to a reading of Frankenstein, in translation through illustration and comics adaptation, two forms which rely upon the interaction of words and pictures to create an impression of the novel which is mediated by the imaginative reception of the text, or its afterlives, by the illustrator or cartoonist. This essay will begin [MOU5] by discussing, generally, the history of illustration of the novel and adaptations into the medium of comics and will then segue into a discussion of two particular projects, the illustrations of Bernie Wrightson to an edition of the novel published first by Marvel in the 1980s, and re-issued by Dark Horse Books in 2008, and an issue of The Crypt of Terror, in which Al Feldstein (writing) and Jack Davis (Penciling) relay an iteration of the Frankenstein story. Throughout, I will gesture also to translation of the novel in general and to some of the multifarious adaptations which have contributed to the textual afterlives of Mary Shelley’s masterpiece, including her own additions and emendations which, in the 1832 edition, significantly altered the meaning and influenced the interpretation of the text with the presumption of authorial authority but which, as with all such projects, amounts also to a project of translation.[MOU6]

The project of cataloguing the history of illustration of Frankenstein, as well as adaptations and translations has largely been undergone, and interested readers are advised to turn to those authors cited for more exhaustive accounts[MOU7] . It suffices, here, to provide a few illustrative examples and provide a broad overview, to the end of enlightening the forthcoming discussion of illustration as translation. Emily Alder notes that the first translation of the 1818 text was into French in 1821, just two years before Richard Brinsley Peake’s 1823 stage adaptation Presumption; or, the Fate of Frankenstein (210).

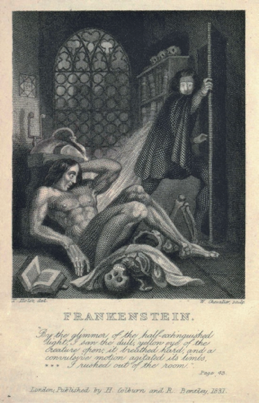

The first illustrated edition dates to 1831 which was a part of the Henry Colburn, and Richard Bentley Standard Novels Series, its ninth publication, and the third edition of the novel (Moreno and Moreno 228). It was illustrated by Van Holst, a pupil of Fuseli whose paintings had an impact on Shelley’s composition, and whose frontispiece is illustrative of his approach, in that his creature is comely and decidedly un-Karloff-ian, and looks bewildered, surrounded by Gothic detritus, as Victor flees his chamber in disgust (Fig. 1). As Moreno and Moreno note, too, this first illustrated edition did much to counteract the trend, which would become prominent in dramatic revivals of Shelley’s tale, to create the countercurrent [MOU8] in artistic trends of depicting the monster as more Adam-like and less like the green grotesquerie of Peake’s play (231).

Another intriguing instance is the 1897 London and Philadelphia edition of the novel which featured no portrayals of characters in the novel at all, only a collection of landscapes[MOU9] , suggesting the uniquely (R)omantic nature of the text with its own lengthy digressions into Shelley’s travel diaries and quotations of picturesque poetry, and choosing, rather than to render the instances themselves, to juxtapose them with countervailing images in what Scott McCloud in Understanding Comics, would refer to as “Parallel” in which image and text are not, at least in the perception of the frame, related[MOU10] to one another[MOU11] (154).

The De Luxe Edition of 1932, illustrated by Nino Carbé, takes influence from Murnau’s Nosferatu, and portrays the creature as something more vampiric, showing the influence not only of the Universal monster films featuring the creature, but also the vogue for vampirism that was encapsulated by the popularity of Lugosi’s portrayal of Count Dracula (Moreno and Moreno 232). Lynd Ward’s 1934 woodcuts are a standby for critical exploration of the illustrative tradition of Frankenstein, and are executed in woodcuts (Moreno and Moreno 234). Notably Ward includes an albatross in his illustration accompanying Walton’s quotation of Coleridge, thus undergirding the intertextuality of Shelley’s text, and his images also comment notably on the story by providing visual cues to later events, including using caricature of the judges in Justine Mortiz’s case as “grotesque and simian” to suggest the imminent outcome (Moreno and Moreno 234).

Finally, the 1968 Cercel des Bibliophiles edition published in Geneva, notably introduced by a film critic rather than a literary critic in a nod to the “pluritextuality” which by this point had allowed Boris Karloff with his flat head and neck bolts to supplant the “original.” It is illustrated by Christian Broutin, who, as the Morenos note, includes Shelley as a lurking figure in his illustrations alongside the monster, evoking the ‘hideous phantasm’ of the preface to the 1831 edition, that inspired the tale, pointing also to the idea of Shelley as a presence in the text (interfering with and changing it, as she did in 1831), which could, in some ways, be considered tampering in the mode of her ill-fated Frankenstein, or even be seen as a kind of self-translation, with all of the implicit pitfalls of that act[MOU12] (235).

In sum, as Paul O’Flinn conjectures, there is no definitive version of Frankenstein [MOU13] and its myriad adaptations have, as echoed in Denson, precipitated a “literal rewriting [..] as novel becomes script becomes film” becomes illustration, becomes comic, as this essay will expound (194-5). Even as early as Peake’s 1823 play, Shelley began to feel that “the notoriety of the story owed as much to Peake’s stage adaptation as to the text itself, if not more” (O’Flinn 201). This could, of course, send one down a rabbit hole of deconstructionist argumentation, but I argue, along with O’Flinn and Denson, that the very fact of Frankenstein’s appropriation makes questions of originality of the text hard to argue[MOU14] , particularly if one measures the worth of a literary work by its influence, as indeed, there can be no objective assessment of quality, and influence is required to even grace the desks of readers who might lend a work a stamp of quality. In essence, adaptation must, at least in a sense, be seen as a kind of translation, with the Karloff films as valid an entry in the ‘canon’ of Frankenstein as the film, just as Shelley’s 1831 edition was undoubtedly fed by Peake’s play, making the question of the original, even in Shelley’s lifetime, a thicket. [MOU15] O’Flinn argues that emending the text in 1831 to renounce Elizabeth’s status as Victor’s cousin is as much an act of translation, not between but within a language, as later versions increasingly confusing, or translating entirely, the creature into the creator, as the creature usurps the name of Frankenstein in most popular media (202).

By way of example, O’Flinn cites Bertholt Brecht, who often revised his plays depending on the context in which they were performed, with the production of Galileo that followed close on the heels of the nuclear holocaust visited upon Hiroshima and Nagasaki, being coloured by those events, casting the father of physics’ life in a new light, and, to Brecht required staging (illustration, if you will) which could highlight this context and lend the production not only the aura of timeliness, but also acknowledge Brecht’s belief that theatre must imitate reality to have import.

Even during the composition of the novel, Shelley was deeply affected by news of Luddite uprisings and retributions (O’Flinn 197). Percy Shelley wrote a pamphlet which Mary notes she read in her diary, called An Address to the People on the Death of Princes Charlotte from November 1817 lamenting the ‘national calamity’ of a country torn between revolt and the vengeful despotism of the government response, which Percy Shelley characterized as ‘the alternatives of anarchy and oppression’ a stance which echoes strongly his response to the 1819 Peterloo massacre, in Masque of Anarchy (O’Flinn 199). O’Flinn notes a number of textual occasions wherein Shelley was responding, directly or indirectly, to these political contexts, much like Brecht, and so it seems only natural that her emendations in response to the changing politics of 1831 Britain as opposed to that of 1818, no less than her own evolution in her political thought, should be thought as much an act of translation as Brecht restaging or rewriting to complement his own historical context. [MOU16]

To return to illustration, another example, and one which hews closely to the quality of Wrightson’s work which I will explore later, the 1984 Pennyroyal edition of the novel, like Ward’s, uses the medium of woodcut illustration, again with the intention of mediating the interpretation of the text through its juxtaposition with his images (Bukaman 192). The most notable choice therein, is that his accompaniments to the chapters narrated by the creature, seven images in total, are a succession of increasingly magnified views of the creature’s face set against a matte black background (Bukatman 204). Of further interest, still, is the fact that these seven images are the only ones printed in colour in the entire volume, and this merely a tinge of gold which, Bukatman argues, suggests the fire between the creature and the creator hearing the tale, the reiteration driving home Moser’s interpretation that the only thing which separates man from monster is this fire, this Promethean gift (204). Moser also, quite intriguingly, gives over the final image to the face of the creature in death, effectively giving it not only the final speech, but the final image in the text, signaling the side which the illustrator has taken[MOU17] , even if it does “mis-translate” the stated intentions of Mary Shelley herself (Bukatman 205).

Translating through illustration, much like adapting into film, implies not only the change of media, but also of audience[MOU18] . As O’Flinn notes of the adaptation of a Gothic novel pitched to the emergent middle class whose genre the novel was, into the film, which by the 1930s was the common media of the people, a proletarian art or entertainment is a kind of translation of itself. By the same token, the illustrated novel, generally produced at a much higher cost than the pulps of the 1950s whose content aped so much of the Gothic aesthetic and character and costlier too than cheaply produced paperbacks, even today, suggest that it is pitched, like the novel of Shelley’s time, to an audience with disposable income, and, by extrapolation, education. [MOU19] Illustration is a prestige format extended, even today, primarily to expensive works and towards an audience that can afford them, with even children’s books that have scarcely more than 20 pages, costing more than an average hourly wage. This is by comparison to comics, like film a historically proletarian medium, which I will extrapolate upon below.

In translating a ‘horror’ novel, to run the risk of assigning Frankenstein a genre, one must consider the effect which must be produced by the work to affect its ends. Scott Bukatman makes the argument that neither illustration nor comic should have the capacity to scare, because the reader is in control of the pace at which the images are presented to them and can escape the experience entirely with a mere fluttering of the eyelids (191). This is distinct from film, which presents the images in the sequence and at the exact time the director (or editor) wishes, and which, even if one closes one’s eyes, subjects us still to the sound of what we fear to look upon. The same, too, is true of theatre, where the performers, and the director, again control the pace of the action and what the audience “sees” at any given moment. Bukatman concedes, however, that the novel (which can also be shut out and the pace of intake of which is controlled by the reader) can couch the horrific in language which leads one unexpectedly (as in the case of Shelley’s florid prose giving way to linguistic renditions of charnel houses and exhumed remains) to dawning horror. Illustrations, assuming they accompany and represent the text they illustrate, and comics especially, have the “disadvantage” of being taken in as a whole before being read sequentially, such that the reveal, two panels, or even a page away, is spoiled the moment the reader turns the page, such that only by hiding the reveal behind a page flip can the cartoonist conceal the horrific moment.

And yet, the comic, at least in the 1950s with the prominence of EC (Entertaining Comics – changed from the publisher’s father’s corporation, Educational Comics), most notably its horror titles, including Crypt of Terror, an issue of which I discuss below, and since the 1980s with the publication of the influential Alan Moore, Steve Bissett, John Totleben, and Rick Veitch run on Swamp Thing (taken over from Bernie Wrightson penciling scripts by Len Wein) was the principle medium for horror content. Bukatman sheds some light on this seeming paradox, arguing that illustration, and comics in particular, have the strength of fascinating the reader, allowing them, unlike the frame in a film which is replaced by another in less than 1/24th of a second, to linger over the image and to take in detail at their own pace, much like the text of the novel. As he puts it

the reader encounters a particularly striking, startling or even shocking image or image sequence in the course of reading, and moves on. Until she doesn’t. The page that is turned can also be turned back, to look again. And again. And, tomorrow, again. A picture can be very haunting (especially for a kid who isn’t yet allowed to watch horror movies, or in the days before home and streaming video made cinema perhaps overly accessible). Ostensibly depictive, a picture can play with shadows and light, hiding and revelation. An image might even dare a reader/viewer to confront it again, the challenge being to somehow master the feelings it stimulates. One could say that images in books and comics do more than haunt, they lurk between the pages, waiting to emerge and re-emerge. (191)

This[MOU20] applies equally to comics as to illustration, and, though Bukatman argues comics are closer to cinema in keeping images moving constantly before the eye, his reasoning here seems specious. In comics, as McCloud talks about in the chapter on the “gutter” or the space between panels of a comic, this gap creates a space in which the action between the panels can occur, such that a man with an axe in one panel, who, by the next is holding a severed head, leaves no doubt as to what has occurred. This is akin to Bukatman’s argument that illustrations in a book “punctuate” the text, approximating a game of hide and seek analogous to the jump scare in a film (192). In both cases, the addition is clearly, if not necessarily to the benefit, then certainly to the augmentation of the story [MOU21] even if it is as strictly “faithful” like one of the many Classics Illustrated comics titles marketed as introductions to works of classical literature on par with the Romantic endeavor of Charles and Mary Lamb to introduce young readers to the tales of Shakespeare[1]. In doing so, this act of translating, abridging being another term, or otherwise adapting the earlier work, the new author or illustrator or cartoonist creates a version in canon with the original, though perhaps no more or less legitimate[MOU22] than that original. Bukatman refers to a story in Mike Mignola’s Hellboy series which incorporates the creature as a character and which takes place in the fictional continuity, before the novel was even written and he says that “Comics once more turn the novel into another, rather than the first, iteration of the monster’s story” (201). A Marvel comics story Denson remarks upon has the X-men squaring off against a creature whom professor X asserts was the model for that in the novel. It may then seem absurd to counter the “original” 1818 text with versions patently created later and influenced by it, but from a critical standpoint, it is no more ludicrous than the acknowledgement of influence generally, and Mary Shelley’s tale of a “hideous phantasm” compelling her to set its visage into text.[MOU23]

Emily Alder offers another intriguing perspective on the translation of Frankenstein into later, particularly illustrated texts, taking for her prime example, a children’s picture book entitled Do Not Build a Frankenstein!. Alder suggests that, much like the Lamb’s Tales from Shakespeare, Frankenstein can be used as a textual referent in books for younger readers: “if writing in Gothic modes can offer, shape, or negotiate new constructions of childhood that understand both child characters and implied child readers as sophisticated, capable, critical, and knowing, so too can graphic novels and picturebooks, because graphic narratives communicate in different ways from text-only narratives, their forms offer some unique opportunities of escape from traditional conventions or expectations” (213). In this example, Alder’s representative text tells the story of a little boy who has created the creature as a playmate and its appearance is closely modeled on the monster of Whale’s film. The text, as Alder presents it, “relies on awareness or prior knowledge of an originating story to exploit readers’ expectations, a trick dependent on pictures, words, and the material form of the book itself (215).” The title pages show children running away from something underneath the foreboding title itself, suggesting how the story will unfold, and, indeed, the Victor character has moved to a new town and school to escape it, explaining to his classmates, like the novel’s Victor does to Walton, what he has done. The pictures contradict the words of the text, however, showing the creature, “misunderstood and playful” unintentionally terrifying Victor in the night, breaking his toys, and scaring his friends (216). By the story’s close, as Alder notes, the title page has assumed a new context, as it is revealed the children are playing tag with the creature rather than fleeing its rage (216). McCloud would call this an example of “inter-dependent” comics communication, in which neither word nor image can convey the whole idea by themselves, and the book, in addition to relying on some prior knowledge of the story being subverted, exercises its point by having the words and pictures in semi-opposition to one another, much as one could imagine an illustrated Frankenstein, like Van Holst’s in which the creature isn’t ghastly in the slightest, creating tension with the text as written and changing, or translating the story.[MOU24]

Within the text itself, the creature presents itself as lost in translation, unable to impress upon viewers the wholeness of his human character[MOU25] . He is a glyph which the sighted cannot abide long enough to see translated, creating a tension wherein the monster, even narrating his own story, is, in fact, narrated by Victor to Walton and, in turn, by Walton, to his sister, or the reader. As Diedrich says, “all of the monster’s interlocutors–including, finally, the reader–must come to terms with this contradiction between the verbal and visual” [MOU26] (404). This feeds further into Denson’s claims that “non-diegetic traces of previous incarnations accumulate on such characters, allowing them to move between and reflect upon medial forms, never wholly contained in a given diegetic world” (531). Just as the monster is unable to proceed into the world, nor is anyone, really, without being prejudged based on his appearance, so, too, is a reader, even in Shelley’s lifetime, incapable of approaching the text without the weight of “non-diegetic” traits creeping into their assessments, try how the new critics might.[MOU27]

Which brings me to Bernie Wrightson[MOU28] . Having approached the task of illustrating Shelley’s novel as a passion project in his spare time over many years as a successful penciller and inker of monthly comics, his stated aim was to produce illustrations unencumbered by the other visual, particularly filmic, adaptations of the text. He stated “ I loved the movie interpretation and I’ve been fascinated with that story ever since” however, as Wrightson admitted in an interview, cited by the Morenos, “When I was a little older, I read the book by Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley and wondered why they never put all that great stuff into a movie” (236-8). Wrightson’s illustrations, in the Morenos’ words, “reveal sublime isolation and melancholic solitude” reflecting the influence of Romanticism as embodied by the Caspar David Friedrich painting The Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog, which has graced the cover of more than one edition of the novel (238). Wrightson’s illustrations, executed in pen and ink, reproduce in exacting detail the quality of pristine woodcuts, with hatching and value work heavily indebted to the woodcuts Gustav Dore executed for The Rime of the Ancient Mariner (Richardson).

Turning to the endpapers for the Dark Horse reissue of Wrightson’s edition of the novel, the first character encountered is the creature surrounded by forest, his face pensive, suggesting we have encountered him during his sojourn with the Delaceys. The cover, too, bears a detail shaped like a Victorian miniature, of the final illustration, before the rear endpapers, of the creature following Victor’s demise. Both signal, from the outset, that the attention in this, as in many versions of the tale, will be upon the creature, rather than upon Victor. The illustrated title page is of a graveyard bedecked with angels, eyes uplifted, and grasping cherubim, with the author credits placarded to a headstone topped with a down-looking skull wearing a crown of thorns, suggesting a desiccated Christ. The first illustration accompanying the text shows Walton standing amongst the rigging of his ship, the sky hatched to suggest clouds just as in a woodblock, with delicate curving linework shading the sails. In a way, the image seems to be a reverse perspective of Friedrich’s famous painting. Only Walton’s face is aglow with the light piercing the clouds, his long hair blowing in the wind and his solitary figure clearly evoking the romantic solitary of Friedrich’s ideal (Shelley and Wrightson 10)

Wrightson’s illustrations often rely on scale for their effect. In his rendition of the scene captioned “I beheld a stream of fire issue from an old and beautiful oak…” (37). Victor is dwarfed not only by the phantom image of the tree beyond the door he holds ajar which is awash in firelight or lightning glow, but by the house itself. The doors are three times his height and the adjacent draperies are drawn shut. The ceiling is beyond the frame as even the semicircular glass window which caps the threshold is cut off, its spider-web patterned glass suggesting its design was inspired by shattering, by the picturesque aesthetic of follies painted by Fuseli, and landscape architecture a la Capability Brown, with its delight in the “ruined.”

The lecture hall in which Victor is subjected to “a recapitulation of the history of chemistry” is similarly Brobdingnagian with only four students in view, outnumbered by the engraved faces of the great scientists which adorn the bottom of the wooden lecture seating (43). The professor, back turned to the viewer, holds the book behind him, orating from memory, evidently, standing beside a small assortment of vials and lab equipment, but with his hand set upon much thumbed tomes, bookmarks protruding, suggesting the distaste Victor will feel for this impractical method of teaching the natural sciences. Most of the laboratory equipment is arrayed along the top of the pews beneath the tall banks of windows which are slatted in geometric patterns, curves, squares, and rectangles, indicating the dominance of rationality and science in this hall of learning, as opposed to the romantic and the picturesque of Victor’s home.

By comparison, Victor’s apartments are littered with equipment, with glassware and practical instruments, but the books, with the exception of the one in which he is writing in Wrightson’s illustration, are bundled, tied, clasped, or stacked beneath such instruments (49). This is the laboratory of a practical man, in which his laid-back posture, feet extended beneath the cluttered dining table, suggests a bizarre ease in the presence of a coffined skeleton and a skull ornamentally displayed on an adjacent shelf, harbingers of the work Frankenstein will soon undergo.

Wrightson’s first illustration of the creature bears a skull in the upper left, capping a long piece of laboratory glassware, looking down upon the creation like a spectre of death (59). The creature grimaces, its lips drawn back from two rows of neat white teeth, its hair hanging in thin strands from its head, its face chiseled to the ideal of human perfection with nary an ounce of fat to be found. Its nose, however, is receded, skull-like, suggesting Wrightson’s creation for comics, the Swamp Thing, and its muscled form is uncanny, every sinew drawn taught, forcing the veins to the surface like a body-builder’s as it grips the railing of its coffin with an unnaturally bulky hand. The image is captioned “… I had selected his features as beautiful.”

In the scene of their meeting on the mountaintop, Wrightson’s Victor and the creature take up only the top third of the composition, with semi-horizontal hatching on the sky beyond suggesting the extreme wind which billows their clothes (104). Victor holds a staff before him in protection against the towering creature whose face appears like a hollowed skull, impassive like the personification of death, sans scythe, arms at its sides. The rest of the composition is taken up with the surface of the glacier or mountain, with the crags which might be crevasses waiting to swallow creator and created alike.

The scene of the creature’s first glimpse of itself in the pool shows no reflection in the hatched surface of the river as the monster’s huge forearm enwraps a boulder as though for dear life and leans upon the other, its face downcast, eyes closed in evident dismay at what it has glimpsed. It’s black cloaked form bleeds into the surrounding moonlit foliage (125). The creature’s affectation is almost effete in the scene where it peers through the chink in the Delacey’s wall, it’s right hand coiled in the semblance of a gesticulation as its brawny left arm holds it upright and its thin lips curve ever so slightly upward in a show of peace as its hair hangs damply from its forehead and its eyes, white in the glow of the Delacey’s hearth-fire seem expectant and hopeful, its legs splayed in girlish delight at the possibilities of what, by rights, is the creature’s adolescence (131). Finally, in the closing end-papers, Wrightson shows the wave wracked sea bleeding almost indiscernibly into the ice floe where the creature, now arrayed in fur lined clothes that all but hide his inhumanity, save his massive hand and cape wrapped face (even its hair is combed to appear somewhat dapper) looks down at its shadow as Walton’s ship crosses the white horizon.

All of these illustrations, though I have selected only a few, suggest the task Wrightson undertook as illustrator, as translator. Not only has this edition notably left out either of Shelley’s prefaces, though the first is likely the product of her husband’s pen and replaced them with an introduction by Stephen King, Wrightson has also foregrounded the creature as the hero of the text, like Moser, giving it the last visuals, and also the first visual, as well as the final words, though they are mediated through Walton. It is no accident, to say the least, and Wrightson was fully aware of the tradition into which he stepped, coloured, if not in his visual approach, then certainly in his narrative allegiance to the creature who had been the highlight of the film that first drew him to the novel, just as the green grotesque of Peake’s play attracted many readers to Shelley’s novel when the theatre was the proletarian art and the novel the prestige form to which the lower middle and lower classes aspired.[MOU29]

Finally, I turn briefly to The Crypt of Terror, issue 34, in which the first story, following the traditional introduction by the eponymous Cryptkeeper, follows the reader, “you” rather, as “you” wake in the laboratory of a mad scientist, finding yourself bound, and in which “you” as the captions attest, escape the laboratory, find yourself in the center of town where the townspeople, gathered to enter the theme-park-cum-carnival which “you” later discover is the front for the laboratory of the scientist who has created you in the likeness of Frankenstein’s monster, reanimating your corpse after you died of a heart attack in the house of horrors attraction, from fright, evidently. The story, written by Al Feldstein and penciled by Jack Davis of Mad fame, also published by EC, is not a strict adaptation of Shelley’s story, but is a retelling with clear reference to that original tale, much like the Marvel comics which Denson examines in his essay. Davis’ creature is well within the Karloff mold, complete with flat head, hair, and protruding bolts. The story diverges, however, in the fact that the creature has memories of a previous life, even stealing a car after inadvertently strangling its frightened driver, and driving to its erstwhile home where its wife, not recognizing the reanimated corpse of her beloved, flees and ultimately falls from a window as she attempts to escape, dashing herself against the concrete patio below. The creature then returns to the lab where its decidedly un-Frankensteinian creator had hailed its reanimation as a triumph and where it is greeted in with open arms. It strangles the madman and wanders back into the wax museum of horrors, finding itself, “yourself” rather, confronted by a tableau of the monster of Shelley’s creation which turns out to be a mirror. Finally, “you” flee the renewed mob into a house of mirrors where the sight of your own reflection at every turn drives you mad and, ultimately, kills you, as the horrors of the wax museum killed your previous self. The hag-like Cryptkeeper intrudes at the end of the tale to comment with a pun on the idiom “if looks could kill” and admonishes “you” the reader, illusion broken that you were, in reality, the creature of this tale, not to look into a mirror for fear of what you might see.

There are many layers to this story, only eight pages as was typical of stories in EC magazines, and as Alder read into a children’s book, much can be read into this comic with its dependence, not only upon familiarity with the “original” story of Frankenstein, as referenced in the comic, but also with the various film adaptations. The comic is as intertextual as Shelley’s novel, though its referents are different. The conceit, too, of placing the reader in the position of the creation signals a translation of Shelley’s novel, too, in that it takes the sympathy with the creature to an even greater extreme[MOU30] , not only asking you to rectify the contradiction between verbal and visual which Diedrich highlights, but asking you to embody it. The story denies you, for the most part, the experience of witnessing the monstrosity of “you” the creature, except through the eyes of those who fear and shun you, forcing you into the position of the creature in the novel, [MOU31] while also removing the dual layers of abstracting narrative which couch the creature’s autobiography in Shelley’s text. Davis and Feldstein pare down the story to its essentials[MOU32] , taking the same tack as Wrightson and countless others, including the artists behind Do Not Build a Frankenstein! and refuse to simply narrate the experience of the creature in the reflecting pool by simulating it with a mirror, inviting the reader not to read it but to experience it, to experience the sensation of, Eve-like, gazing at one’s reflection and not recognizing it, though this is mixed in with the memories of a prior life which “you” have in the story.

Ultimately, the question of what constitutes an act of translation, if we accept the possibility of such within a language, is open ended. I would argue, however, that the fact of stories being “interpreted” by any given reader, suggests that language is always an act of attempted communication subject, as the creature is, to being misjudged on sight. In essence, any failure of communication is, ipso facto, a failure of translation. Frankenstein epitomizes the romantic novel in its intertextual gestures to contemporary works and themes, and in its encapsulation of many of the aesthetics, whether original or accrued, which the modern reader ascribes to Romanticism as such. Illustration and adaptation into comics are only two ways in which the story has penetrated subsequent culture and are, I argue, illustrative of the story’s supreme adaptability to different contexts. If for no other reason than the eternal question of what is the “original” Frankenstein, as scholars to this day debate the degree to which Percy Shelley contributed to, edited, or emended his wife’s text, leaves the work in a limbo which epitomizes the “plurimedial” quality Denson points to in Frankenstein and other habitually adapted works. Wrightson’s illustrations are not unique in their approach to the text as itself, eschewing prefaces (though a new introduction was added for the Dark Horse release) and aesthetic qualities borrowed from the popular films, but they do highlight a quality in illustration, of this text in particular, wherein illustrations not only render the text into image, but also implicitly take sides in the conflicts depicted[MOU33] , giving extra-textual voice to certain characters that doesn’t adapt, so much as translate, the “original.”

Fig. 1

Works Cited

Alder, Emily. “Our Progeny’s Monsters: Frankenstein Retold for Children in Picturebooks and Graphic Novels.” Global Frankenstein, edited by Carol Margaret Davidson and Marie Mulvey-Roberts, Palgrave MacMillan, 2018, pp. 209-226

Bukatman, Scott. “Frankenstein and the Peculiar Power of the Comics.” Global Frankenstein, edited by Carol Margaret Davidson and Marie Mulvey-Roberts, Palgrave MacMillan, 2018, pp. 185-208

Davison, Carol Margaret, and Mulvey-Roberts, Marie. Global Frankenstein. Palgrave Macmillan, 2018.

Denson, Shane. “Marvel Comics’ Frankenstein: A Case Study in the Media of Serial Figures.” Amerikastudien / American Studies, vol. 56, no. 4, 2011, pp. 531-553.

Diedrich, Lisa. “Being-Becoming-Monster: Mirrors and Mirroring in Graphic Frankenstein Narratives.” Literature and Medicine, vol. 36, no. 2, 2018, pp. 388–411.

Moreno, Beatriz González, and Fernando González Moreno. “Beyond the Filthy Form: Illustrating Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein.” Global Frankenstein, edited by Carol Margaret Davidson and Marie Mulvey-Roberts, Palgrave MacMillan, 2018, pp. 227-243

O’Flinn, Paul. “Production and Reproduction: The Case of “Frankenstein.” Literature and History, vol. 9 no. 2, 1983, pp. 194-213

Richardson, MikePersonal Interview. 27 February, 2019.

Shelley, Mary Wollstonecraft, et al. Frankenstein, or, The Modern Prometheus. 1st ed., Dark Horse Books, 2008.

[1] In the interest of fully representing Bukatman’s thoughts on comics as a medium particularly for the translation, adaptation, or continuation of Frankenstein, I provide the following extended quotation. “If there is as perfect an equivalent in comics, one that exemplifies something fundamental about the medium, I have yet to find it. But perhaps that’s the point: perhaps no single text speaks to the uncontainable variation of comics. The medium not only combines word and image but pictorialised words and legible images. The use of language varies, as does the style of drawing. Further variety arises from the treatments of panel, page, story length (from single panels or pages to the 100-year continuing saga that is Gasoline Alley), the dimensions of the physical book, the paper choices and the presence or absence of colour. Comics are difficult to encompass and define; they are best understood in their multiplicity. The plurality of Frankenstein comics’ adaptations and continuations begins to suggest the range of strategies that characterise the medium. Comics offer multiple modes of narration (descriptive captions, speech balloons, wordless comics) that make it particularly appropriate for the adaptation (or continuation) of Shelley’s Frankenstein, with its multiple narrators. Comics also have a unique capacity to depict thought, whether through dialogue, ‘voice-over’ narrative captions or thought balloons. Dialogue and narration, though not their visualisation, are also characteristic of prose and cinema, but thought balloons are unique to comics. Michael Marrinan finds in these the epitome of literature’s ‘free indirect discourse.’4 In this rhetorical mode, ‘certain material configurations of language generate representations of another person’s thoughts without positing a fictive, all-knowing character or narrator’ (Bender and Marrinan 2010: 72–3). In the service of modernist experimentation, some authors further devised complicated sets of shifters to allude, on the written page, to the non-linguistic nature of thought. In the thought balloon, comics have ‘a very specific and graphic way of marking this phenomenon without all the difficulties presented to writers’ (Bender and Marrinan 2010: 72–3). (Bukatman 193)”

[MOU1]Nice discovery. You could make more of this link. Or at least introduce it in a way so it is more foregrounded.

[MOU2]Sentence fragment

[MOU3]Meaning “non-narrative”?

[MOU4]Do you mean that the canonical status belongs to the “story”/”myth” of Frankenstein or Sherlock Holmes, and not exclusively to the original text?

[MOU5]You have a focus here, though I don’t see a thesis as such. But let’s see what happens in what follows ….

[MOU6]Great point. So we can think of a new edition as a sort of translation.

[MOU7]Fair enough

[MOU8]“counteract” and “countercurrent” make this sentence hard to unpack!

[MOU9]This is interesting!

[MOU10]So the illustrated landscapes are not necessarily ones portrayed in the novel? Interesting.

[MOU11]This long sentence could be broken up into at least smaller ones.

[MOU12]Can revised versions be seen as a sort of translation? Some writers literally translate their own work and revise it in the process.

[MOU13]OK, good. I was beginning to wonder what the point of this whirlwind tour was.

[MOU14]This sounds very deconstructive!

[MOU15]Ok, so there is a “Frankenstein canon,” in the sense of a broadly established/agreed upon (but by who?) set of texts from various genres and even media that tell the story of Frankenstein? And this makes moot the idea of an official text (the novel) with a certain authority? I can buy that. But you might highlight your claim by evoking the objections to it. These might be simple (e.g. the real Frankenstein is the novel, everything else is derivative) or sophisticated (e.g. the novel is an astonishing feminist text, which not all other versions are; and more generally, how does this claim handle the issue or significant differences between iterations/versions?)

Textual scholarship has, of course, long pondered the implications of the fact that any literary text exists not as one entity but rather as various versions (manuscript drafts, typescript drafts, versions with a writer’s approval, versions with an editor’s approval, published versions, revised versions) all of which interact with each other. Your focus is slightly different, and a contrast could also help bring out what you are getting at.

[MOU16]Certainly, it is conditions such as this that give the lie to the idea of “Authorial intention” as a unified, consistent origin for a literary work. Not that writers don’t have intentions. They do. But their intentions are not any simpler or easier to define than the things they write.

[MOU17]I’m not sure what the point of this parag is. Is this it?

[MOU18]Good point!

[MOU19]I get the general point, but this sentence loses me …

[MOU20]Antecedent unclear.

[MOU21]What’s the difference? What do you mean by augmentation exactly?

[MOU22]How is a legitimate text in a canon defined?

[MOU23]Interesting. Perhaps the conflict here is dispelled by a distinction between historical priority and narrative priority.

[MOU24]Good.

[MOU26]Why, exactly?

[MOU27]Do you mean that it is nearly impossible to read the novel without having in mind the visual image of the creature as portrayed in texts outside the novel?

[MOU28]What is the logic of the transition? How is your discussion of Wrightson’s illustrations going to advance your argument?

[MOU29]Your account of the Wrightson illustrations is detailed But I have been waiting for the upshot of it all. But I’m still not sure I’m any the wiser.

[MOU30]Good point.

[MOU31]If the creature is portrayed in the comic, then the reader can see it without the aid of a mirror. This contradicts the use of the second person personal pronoun “you.”

[MOU32]But what are these? It’s a big question!

[MOU33]This seems important.